BSG, Fifteen Years On

It’s been called to my attention that the last episode of the “new” Battlestar Galactica aired fifteen years ago yesterday?

My favorite part of that finale is that you can tell someone whose never seen it that the whole show ends with a robot dance party, and even if they believe you, they will never in a million years guess how that happens.

And, literally putting the words “they have a plan” in big letters in the opening credits of every episode, while not ever bothering to work out what that plan was, that’s whatever the exact opposite of imposter syndrome is.

Not a great ending.

That first season, though, that was about as good a season of TV not named Twin Peaks has ever been. It was on in the UK months before it even had an airdate in the US, and I kept hearing good things, so I—ahem—obtained copies. I watched it every week on a CRT computer monitor at 2 in the morning after everyone else was asleep, and I really couldn’t believe what I was seeing. They really did take that cheesy late-70s Star Wars knockoff and make something outstanding out of it. Mostly, what I remember is I didn’t have anyone to talk about it with, so I had to convince everyone I knew to go watch it once it finally landed on US TV.

It was never that good again. Sure, the end was bad, but so was the couple of years leading up to that end? The three other seasons had occasional flashes of brilliance but that mostly drained out, replaced by escalating “what’s the craziest thing that could happen next?” so that by the time starbuck was a ghost and bob dylan was a fundamental force of the universe there was no going back, and they finally landed on that aforementioned dance party. And this was extra weird because it not only started so good, but it seemed to have such a clear mission: namely, show those dorks over at Star Trek: Voyager how their show should have worked.

Some shows should just be about 20 episodes, you know?

Book Lists Wednesday

Speaking of best of lists, doing the rounds this week we have:

We give the Atlantic a hard time in these parts, and usually for good reasons, but it’s a pretty good list! I think there’s some things missing, and there’s a certain set of obvious biases in play, but it’s hard to begrudge a “best american fiction” list that remembers Blume, LeGuin, and Jemisin, you know? Also, Miette’s mother is on there!

I think I’ve read 20 of these? I say think, because there are a few I own a copy of but don’t remember a single thing about (I’m looking at YOU, Absalom, Absalom!)

And, as long as we’re posting links to lists of books, I’ve had this open in a tab for the last month:

Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction - Wikipedia

I forget now why I ended up there, but I thought this was a pretty funny list, because I considers myself a pretty literate, well-read person, and I hadn’t even heard of most of these, must less read them. That said, the four on there I actually have read—Guns of August, Stillwell and the American Experience in China, Soul of a New Machine, and Into Thin Air—are four of the best books I’ve ever read, so maybe I should read a couple more of these?

Since the start of the Disaster of the Twenties I’ve pretty exclusively read trash, because I needed the distraction, and I didn’t have the spare mental bandwidth for anything complicated or thought provoking. I can tell the disaster is an a low ebb at the moment, because I found myself looking at both of these lists thinking, maybe I’m in the mood for something a little chunkier.

The Dam

Real blockbuster from David Roth on the Defector this morning, which you should go read: The Coffee Machine That Explained Vice Media

In a large and growing tranche of wildly varied lines of work, this is just what working is like—a series of discrete tasks of various social function that can be done well or less well, with more dignity or less, alongside people you care about or don't, all unfolding in the shadow of a poorly maintained dam.

It goes on like that until such time as the ominous weather upstairs finally breaks or one of the people working at the dam dynamites it out of boredom or curiosity or spite, at which point everyone and everything below is carried off in a cleansing flood.

[…]

That money grew the company in a way that naturally never enriched or empowered the people making the stuff the company sold, but also never went toward making the broader endeavor more likely to succeed in the long term.

Depending on how you count, I’ve had that dam detonated on me a couple of times now. He’s talking about media companies, but everything he describes applies to a lot more than just that. More than once I’ve watched a functional, successful, potentially sustainable outfit get dynamited because someone was afraid they weren’t going to cash out hard enough. And sure, once you realize that to a particular class of ghoul “business” is a synonym for “high-stakes gambling” a lot of the decisions more sense, at least on their own terms.

But what always got me, though, was this:

These are not nurturing types, but they are also not interested in anything—not creating things or even being entertained, and increasingly not even in commerce.

What drove me crazy was that these people didn’t use the money for anything. They all dressed badly, drove expensive but mediocre cars—mid-list Acuras or Ford F-250s—and didn’t seem to care about their families, didn’t seem to have any recognizable interests or hobbies. This wasn’t a case of “they had bad taste in music”, it was “they don’t listen to music at all.” What occasional flickers of interest there were—fancy bicycles or or golf clubs or something—was always more about proving they could spend the money, not that they wanted whatever it was.

It’s one thing if the boss cashes out and drives up to lay everyone off in a Lamborghini, but it’s somehow more insulting when they drive up in the second-best Acura, you know?

I used to look at this people and wonder, what did you dream about when you were young? And now that you could be doing whatever that was, why aren’t you?

Caves of Androzani at 40

As long as we’re talking about 40th anniversaries, this past Saturday marked 40 years since the last episode aired of “Caves of Androzani”, Peter Davison’s final story as Doctor Who.

One of the unique things about Doctor Who is the way it rolls its cast over on a pretty regular basis, including the actor that plays the title character. This isn’t totally unusual—Bond does the same thing—but what is unusual is that the show keeps the same continuity, in that the new actor is playing literally the same character, who just has a new body now.

The real-world reason for this is that Doctor Who is a hard show to make, and a harder show to be the lead of, and after about three seasons, everyone is ready to move on. The in-fiction reason is that when the Doctor is about to die they can “regenerate”, healing themselves but changing their body.

This results is a weird sub-genre of stories that only exist in Doctor Who—stories where the main character gets killed, but then the show keeps going. And the thing is, these basically never work. Doctor Who is a fairly light-weight family action-adventure show, where the main characters get into and out of life-threatening scrapes every time. “Regeneration Stories” tend to all fall into the same pattern, where something “really extra bad” is happening, and events conspire such that the Doctor needs to sacrifice themselves to save everyone else. And they’re always deeply unsatisfying, because it’s always the sort of problem that wouldn’t be that big a deal if the main actor wasn’t about to leave. There have been thirteen regular leads of the show at this point, and none of their last episodes have been anywhere near their best.

Except once.

In 1984, Doctor Who was a show in decline. No longer the creative or ratings juggernaut that it had been through most of the 1970s, it was wrapping up three years with Peter Davison as the Fifth Doctor that could most charitably be described as “fine”. Davison was one of the best actors to ever play the part, but with him in the lead the show could never quite figure out how to do better than about a B-.

For Davison’s last episode, the show brought back Robert Holmes, who had been the show’s dominant—and best—writer throughout the seventies, but had’t worked on the show since ’79. Holmes had written for every Doctor since the second, but had never written a last story, and seemed determined to make it work.

The result was extraordinary. While most previous examples had been huge, universe-spanning stakes, this was almost perversely small-fry. A tiny colony moon, where the forces of a corporation square off with a drug dealer whose basically space Phantom of the Opera, with the army and a group of gun-runners caught in the middle. At one point, the Doctor describes the situation as “a pathetic little war”, and he’s right—it’s almost perversely small-scale by his standards.

That said, there are enough moving pieces that the Doctor never really gets a handle on what’s going on. Any single part would be a regular day a the office, but combined, they keep him off balance as things keep spiraling out of control. It’s a perfect example of the catalytic effect the Doctor has—just by showing up, things start to destabilize without him having to do anything.

What’s really brilliant about it, though, is that he actually gets killed right at the start. He and new companion Peri stumble into an alien bat nest, which lethally poisons them, even though it takes a while to kick in. Things keep happening to keep him from solving all this, and by the end he’s only managed to scare up a single does of antidote, which he gives to his friend and then dies.

It's also remarkably better than everything around it—not just the best show Davison was in, but in genuine contention for best episode of the 26 seasons of the classic show. It’s better written, better directed, better acted than just about anything else the old show did.

It’s not flawless—the show’s reach far exceeds the grasp of the budget. As an example, there’s a “computer tablet” that’s blatantly a TV remote, and there’s a “magma beast” that’s anything but. But that’s all true for everything the show was doing in the 80s—but for once, it’s trying to do something good, instead of not having enough money to do something mediocre.

My favorite beat comes about 3/4 of the way through, when the Doctor has either a premonition of his own death, or starts to regenerate and chokes it back—it’s ambiguous. Something happens that the Doctor shakes off, and the show won’t do something that weird and unclear again until Peter Capaldi’s twelfth Doctor refused to regenerate in 2017.

It also has one of my favorite uses of the Tardis as a symbol; at the end, things have gone from bad to worse, to even worse than that, and the Doctor, dying, carries the unconscious body of his friend across the moonscape away from the exploding mud volcano (!!), and the appearance of the blue police box out of the mist has never been more welcome.

As a kid, it was everything I wanted out of the show—it was weird, and scary, and exciting. As a grown-up, I’m not inclined to argue.

Nausicaä at 40

Hayao Miyazaki’s animated version of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind came out forty years ago this week!

Miyazaki is one of the rare artists where you could name any of his works as your favorite and not get any real pushback. It’s a corpus of work where “best” is meaningless, but “favorite” can sometimes be revealing. My kid’s favorite is Ponyo, so that’s the one I’ve now seen the most. When I retire, I want to go live on the island from Porco Rosso. * Totoro* might be the most delighted I’ve ever been while watching a movie for the first time. But Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is the only one I bought on blu-ray.

Nausicaä is the weird one, the one folks tend not to remember. It has all the key elements of a Miyazaki film—a strong woman protagonist, environmentalism, flying, villains that aren’t really villains, good-looking food—but it also has a character empty the gunpowder out of a shotgun shell to blow a hole in a giant dead insect exoskeleton. He never puts all those elements together quite like this again.

I can’t now remember when I saw it for the first time. It must have been late 80s or early 90s, which implies I saw the Warriors of the Wind cut, or maybe a subbed Japanese import? (Was there a subbed Japanese import?) I read the book—as much of it as existed—around the same time. I finally bought a copy of the whole thing my last year of college, in one of those great “I’m an adult now, and I can just go buy things” moments. And speaking of the book, this is one of the rare adaptations where it feels less like an “adaptation” than a “companion piece.” It’s the same author, using similar pieces, configured differently, providing a different take on the same material with the same conclusions.

So what is it about this move that appeals to me so much? The book is one of my favorite books of all times, but that’s a borderline tautology. If I’m honest, it’s a tick more “action-adventure” that most other Ghibli movies, which is my jam, but more importantly, it’s action-adventure where fighting is always the wrong choice, which is extremely my jam (see also: Doctor Who.)

I love the way everything looks, the way most of the tech you can’t tell if it was built or grown. I love the way it’s a post-apocalyptic landscape that looks pretty comfortable to live in, actually. I love sound her glider makes when the jet fires, I love the way Teto hides in the folds of her shirt. I love the way the prophecy turns out to be correct, but was garbled by the biases of the people who wrote it down. I love everything about the Sea of Corruption (sorry, “Toxic Jungle”,) the poisonous fungus forest as a setting, the insects, the way the spores float in the air, the caves underneath, and then, finally, what it turns out the forest really is and why it’s there.

Bluntly, I love the way the movie isn’t as angry or depressing as the book, and it has something approaching a happy ending. I love how fun it all is, while still being extremely sincere. I love that it’s an action adventure story where the resolution centers around the fact that the main character isn’t willing to not help a hurt kid, even though that kid is a weird bug.

Sometimes a piece of art hits you at just the right time or place. You can do a bunch of hand waving and talk about characters or themes or whatever, but the actual answer to “why do you love that so much?” is “because there was a hole in my heart the exact shape of that thing, that I didn’t know was there until this clicked into place.”

Cyber-Curriculum

I very much enjoyed Cory Doctorow’s riff today on why people keep building torment nexii: Pluralistic: The Coprophagic AI crisis (14 Mar 2024).

He hits on an interesting point, namely that for a long time the fact that people couldn’t tell the difference between “science fiction thought experiments” and “futuristic predictions” didn’t matter. But now we have a bunch of aging gen-X tech billionaires waving dog-eared copies of Neuromancer or Moon is a Harsh Mistress or something, and, well…

I was about to make a crack that it sorta feels like high school should spend some time asking students “so, what’s do you think is going on with those robots in Blade Runner?” or the like, but you couldn’t actually show Blade Runner in a high school. Too much topless murder. (Whether or not that should be the case is besides the point.)

I do think we should spend some of that literary analysis time in high school english talking about how science fiction with computers works, but what book do you go with? Is there a cyberpunk novel without weird sex stuff in it? I mean, weird by high school curriculum standards. Off the top of my head, thinking about books and movies, Neuromancer, Snow Crash, Johnny Mnemonic, and Strange Days all have content that wouldn’t get passed the school board. The Matrix is probably borderline, but that’s got a whole different set of philosophical and technological concerns.

Goes and looks at his shelves for a minute

You could make Hitchhiker work. Something from later Gibson? I’m sure there’s a Bruce Sterling or Rudy Rucker novel I’m not thinking of. There’s a whole stack or Ursula LeGuin everyone should read in their teens, but I’m not sure those cover the same things I’m talking about here. I’m starting to see why this hasn’t happened.

(Also, Happy π day to everyone who uses American-style dates!)

Jim Martini

I need everyone to quit what you’re doing and go read Jim Martini.

When she got to Jim Martini, he said, I don’t want a party.

What do you mean you don’t want a party, Leeanne said. Everyone wants a party.

Unexpected, This Is

This blew up over the last week, but as user @heyitswindy says on the website formerly known as twitter:

The source article has more clips, but I’ll go ahead and embed them here as well:

I’m absolutely in love with the idea that old Ben has a cooler of crispy ones at the ready, but the one with the Emperor really takes the cake.

This went completely nuclear on the webs, and why wouldn’t it? How often does someone discover something new about Star Wars? According to the original thread, they also did this for other movies, including Gladiator and American Beauty(??!!) Hope we get to see those!

What really impresses me, though, is how much work they put into these? They built props! Costumes! Filmed these inserts! That would have been such a fun project to work on.

Let Me Show You How We Did It For The Mouse

I frequently forget that Ryan Gosling got started as a Mouketeer (complementary,) but every now and then he throws the throttle open and demonstrates why everyone from that class of the MMC went on to be super successful.

I think Barbie getting nearly shut-out at the Oscars was garbage, but Gosling’s performance of “Im Just Ken” almost made up for it. Look at all their faces! The way Morgot Robbie can’t keep a straight face from moment one! Greta Gerwig beyond pumped! The singalong! You and all your friends get to put on a big show at the Oscars? That’s a bunch of theatre kids living their best life.

(And, I’m pretty sure this is also the first time one of the Doctors Who has ever been on stage at the Oscars?)

(Also, bonus points to John Cena for realizing that willing to be a little silly is what makes a star into a superstar.)

Implosions

Despite the fact that basically everyone likes movies, video games, and reading things on websites, every company that does one of those seems to continue to go out of business at an alarming rate?

For the sake of future readers, today I’m subtweeting Vice and Engaget both getting killed by private equity vampires in the same week, but also Coyote vs Acme, and all the video game layoffs, and Sports Illustrated becoming an AI slop shop and… I know “late state capitalism” has been a meme for years now, and the unsustainable has been wrecking out for a while, but this really does feel like we’re coming to the end of the whole neoliberal project.

It seems like we’ve spent the whole last two decades hearing about something valuable or well-liked went under because “their business model wasn’t viable”, but on the other hand, it sure doesn’t seem like anyone was trying to find a viable one?

Rusty Foster asks What Are We Dune 2 Journalism? while Josh Marshall asks over at TPM: Why Is Your News Site Going Out of Business?. Definitely click through for the graph on TPM’s ad revenue.

What I find really wild is that all these big implosions are happening at the same time as folks are figuring out how to make smaller, subscription based coöps work.

Heck, just looking in my RSS reader alone, you have:

Defector,

404 Media,

Aftermath,

Rascal News,

1900HOTDOG,

a dozen other substacks or former substacks,

Achewood has a Patreon!

It’s more possible than ever to actually build a (semi?) sustainable business out there on the web if you want to. Of course, all those sites combined employ less people that Sports Illustrated ever did. Because we’re talking less about “scrappy startups”, and more “survivors of the disaster.”

I think those Defector-style coöps, and substacks, and patreons are less about people finding viable business models then they are the kind of organisms that survive a major plague or extinction event, and have evolved specifically around increasing their resistance to that threat. The only thing left as the private equity vultures turn everything else and each other into financial gray goo.

It’s tempting to see some deeper, sinister purpose in all this, but Instapot wasn’t threatening the global order, Sports Illustrated really wasn’t speaking truth to power, and Adam Smith’s invisible hand didn’t shutter everyone’s favorite toy store. Batgirl wasn’t going to start a socialist revolution.

But I don’t think the ghouls enervating everything we care about have any sort of viewpoint beyond “I bet we could loot that”. If they were creative enough to have some kind of super-villian plan, they’d be doing something else for a living.

I’ve increasingly taken to viewing private equity as the economy equivalent of Covid; a mindless disease ravaging the unfortunate, or the unlucky, or the insufficiently supported, one that we’ve failed as a society to put sufficient public health protections against.

“Hanging Out”

For the most recent entry in asking if ghosts have civil rights, the Atlantic last month wonders: Why Americans Suddenly Stopped Hanging Out.

And it’s an almost perfect Atlantic article, in that it looks at a real trend, finds some really interesting research, and then utterly fails to ask any obvious follow-up questions.

It has all the usual howlers of the genre: it recognizes that something changed in the US somewhere around the late 70s or early 80s without ever wondering what that was, it recognizes that something else changed about 20 years ago without wondering what that was, it displays no curiosity whatsoever around the lack of “third places” and where, exactly kids are supposed to actually go when then try to hang out. It’s got that thing where it has a chart of (something, anything) social over time, and the you can perfectly pick out Reagan’s election and the ’08 recession, and not much else.

There’s lots of passive voice sentences about how “Something’s changed in the past few decades,” coupled with an almost perverse refusal to look for a root cause, or connect any social or political actions to this. You can occasionally feel the panic around the edges as the author starts to suspect that maybe the problem might be “rich people” or “social structures”, so instead of talking to people inspects a bunch of data about what people do, instead of why people do it. It’s the exact opposite of that F1 article; this has nothing in it that might cause the editor to pull it after publication.

In a revelation that will shock no one, the author instead decides that the reason for all this change must be “screens”, without actually checking to see what “the kids these days” are actually using those screens for. (Spoiler: they’re using them to hang out). Because, delightfully, the data the author is basing all this on tracks only in-person socializing, and leaves anything virtual off the table.

This is a great example of something I call “Alvin Toffler Syndrome”, where you correctly identify a really interesting trend, but are then unable to get past the bias that your teenage years were the peak of human civilization and so therefore anything different is bad. Future Shock.

I had three very strong reaction to this, in order:

First, I think that header image is accidentally more revealing than they thought. All those guys eating alone at the diner look like they have a gay son they cut off; maybe we live in an age where people have lower tolerance for spending time with assholes?

Second, I suspect the author is just slightly younger than I am, based on a few of the things he says, but also the list of things “kids should be doing” he cites from another expert:

“There’s very clearly been a striking decline in in-person socializing among teens and young adults, whether it’s going to parties, driving around in cars, going to the mall, or just about anything that has to do with getting together in person”.

Buddy, I was there, and “going to the mall, driving around in cars” sucked. Do you have any idea how much my friends and I would have rather hung out in a shared Minecraft server? Are you seriously telling me that eating a Cinnabon or drinking too much at a high school house party full of college kids home on the prowl was a better use of our time? Also: it’s not the 80s anymore, what malls?

(One of the funniest giveaways is that unlike these sorts of articles from a decade ago, “having sex” doesn’t get listed as one of the activities that teenagers aren’t doing anymore. Like everyone else between 30 and 50, the author grew up in a world where sex with a stranger can kill you, and so that’s slipped out of the domain of things “teenagers ought to be doing, like I was”.)

But mostly, though, I disagree with the fundamental premise. We might have stopped socializing the same ways, but we certainly didn’t stop. How do I know this? Because we’re currently entering year five of a pandemic that became uncontrollable because more Americans were afraid of the silence of their own homes than they were of dying.

Even Further Behind The Velvet Curtain Than We Thought

Kate Wagner, mostly known around these parts for McMansion Hell, but who also does sports journalism, wrote an absolutely incredible piece for Road & Track on F1, which was published and then unpublished nearly instantly. Why yes, the Internet Archive does have a copy: Behind F1's Velvet Curtain. It’s the sort of thing where if you start quoting it, you end up reading the whole thing out loud, so I’ll just block quote the subhead:

If you wanted to turn someone into a socialist you could do it in about an hour by taking them for a spin around the paddock of a Formula 1 race. The kind of money I saw will haunt me forever.

It’s outstanding, and you should go read it.

But, so, how exactly does a piece like this get all the way to being published out on Al Gore’s Internet, and then spiked? The Last Good Website tries to get to the bottom of it: Road & Track EIC Tries To Explain Why He Deleted An Article About Formula 1 Power Dynamics.

Road & Track’s editor’s response to the Defector is one of the most brazen “there was no pressure because I never would have gotten this job if I waited until they called me to censor things they didn’t like” responses since, well, the Hugos, I guess?

Edited to add: Today in Tabs—The Road & Track Formula One Scandal Makes No Sense

March Fifth. Fifth March.

Today is Tuesday, March 1465th, 2020, COVID Standard Time.

Three more weeks to flatten the curve!

What else even is there to say at this point? Covid is real. Long Covid is real. You don’t want either of them. Masks work. Vaccines work.

It didn’t have to be like this.

Every day, I mourn the futures we lost because our civilization wasn’t willing to put in the effort to try to protect everyone. And we might have even pulled it off, if the people who already had too much had been willing to make a little less money for a while. But instead, we're walking into year five of this thing.

The Sky Above The Headset Was The Color Of Cyberpunk’s Dead Hand

Occasionally I poke my head into the burned-out wasteland where twitter used to be, and whilw doing so stumbled over this thread by Neil Stephenson from a couple years ago:

I had to go back and look it up, and yep: Snow Crash came out the year before Doom did. I’d absolutely have stuck this fact in Playthings For The Alone if I’d had remembered, so instead I’m gonna “yes, and” my own post from last month.

One of the oft-remarked on aspects of the 80s cyberpunk movement was that the majority of the authors weren’t “computer guys” before-hand; they were coming at computers from a literary/artist/musician worldview which is part of why cyberpunk hit the way it did; it wasn’t the way computer people thought about computers—it was the street finding it’s own use for things, to quote Gibson. But a less remarked-on aspect was that they also weren’t gamers. Not just not computer games, but any sort of board games, tabletop RPGs.

Snow Crash is still an amazing book, but it was written at the last possible second where you could imagine a multi-user digital world and not treat “pretending to be an elf” as a primary use-case. Instead the Metaverse is sort of a mall? And what “games” there are aren’t really baked in, they’re things a bored kid would do at a mall in the 80s. It’s a wild piece of context drift from the world in which it was written.

In many ways, Neuromancer has aged better than Snow Crash, if for no other reason that it’s clear that the part of The Matrix that Case is interested in is a tiny slice, and it’s easy to imagine Wintermute running several online game competitions off camera, whereas in Snow Crash it sure seems like The Metaverse is all there is; a stack of other big on-line systems next to it doesn’t jive with the rest of the book.

But, all that makes Snow Crash a really useful as a point of reference, because depending on who you talk to it’s either “the last cyberpunk novel”, or “the first post-cyberpunk novel”. Genre boundaries are tricky, especially when you’re talking about artistic movements within a genre, but there’s clearly a set of work that includes Neuromancer, Mirrorshades, Islands in the Net, and Snow Crash, that does not include Pattern Recognition, Shaping Things, or Cryptonomicon; the central aspect probably being “books about computers written by people who do not themselves use computers every day”. Once the authors in question all started writing their novels in Word and looking things up on the web, the whole tenor changed. As such, Snow Crash unexpectedly found itself as the final statement for a set of ideas, a particular mix of how near-future computers, commerce, and the economy might all work together—a vision with strong social predictive power, but unencumbered by the lived experience of actually using computers.

(As the old joke goes, if you’re under 50, you weren’t promised flying cars, you were promised a cyberpunk dystopia, and well, here we are, pick up your complementary torment nexus at the front desk.)

The accidental predictive power of cyberpunk is a whole media thesis on it’s own, but it’s grimly amusing that all the places where cyberpunk gets the future wrong, it’s usually because the author wasn’t being pessimistic enough. The Bridge Trilogy is pretty pessimistic, but there’s no indication that a couple million people died of a preventable disease because the immediate ROI on saving them wasn’t high enough. (And there’s at least two diseases I could be talking about there.)

But for our purposes here, one of the places the genre overshot was this idea that you’d need a 3d display—like a headset—to interact with a 3d world. And this is where I think Stephenson’s thread above is interesting, because it turns out it really didn’t occur to him that 3d on a flat screen would be a thing, and assumed that any sort of 3d interface would require a head-mounted display. As he says, that got stomped the moment Doom came out. I first read Snow Crash in ’98 or so, and even then I was thinking none of this really needs a headset, this would all work find on a decently-sized monitor.

And so we have two takes on the “future of 3d computing”: the literary tradition from the cyberpunk novels of the 80s, and then actual lived experience from people building software since then.

What I think is interesting about the Apple Cyber Goggles, in part, is if feels like that earlier, literary take on how futuristic computers would work re-emerging and directly competing with the last four decades of actual computing that have happened since Neuromancer came out.

In a lot of ways, Meta is doing the funniest and most interesting work here, as the former Oculus headsets are pretty much the cutting edge of “what actually works well with a headset”, while at the same time, Zuck’s “Metaverse” is blatantly an older millennial pointing at a dog-eared copy of Snow Crash saying “no, just build this” to a team of engineers desperately hoping the boss never searches the web for “second life”. They didn’t even change the name! And this makes a sort of sense, there are parts of Snow Crash that read less like fiction and more like Stephenson is writing a pitch deck.

I think this is the fundamental tension behind the reactions to Apple Vision Pro: we can now build the thing we were all imagining in 1984. The headset is designed by cyberpunk’s dead hand; after four decades of lived experience, is it still a good idea?

Friday Linkblog, best-in-what-way-edition

Back in January, Rolling Stone posted The 150 Best Sci-Fi Movies of All Time. And I almost dropped a link to it back then, with a sort of “look at these jokers” comment, but ehhh, why. But I keep remembering it and laughing, because this list is deranged.

All “best of” lists have the same core structural problem, which is they never say what they mean by “best”. Most likely to want to watch again? Cultural impact? Most financially successful? None of your business. It’s just “best”. So you get to infer what the grading criteria is, an exercise left to the reader.

And then this list has an extra problem, in that it also doesn’t define what they mean by “science fiction”. This could be an entire media studies thesis, but briefly and as far as movies are concerned, “science fiction” means roughly two things: first, “fiction” about “science”, usually in the future and concerned about the effects some possible technology has on society, lots of riffing on and manipulating big ideas, and second, movies that use science fiction props and iconography to tell a different story, usually as a subset of action-adventure movies. Or, to put all that another way, movies like 2001 and movies like Star Wars.

This list goes with “Option C: all of the above, but no super heroes” and throws everything into the mix. That’s not all that uncommon, and gives a solid way to handicap what approach the list is taking by comparing the relative placements of those two exemplars. Spoiler: 2001 is at №1, and Star Wars is at №9, which, okay, thats a pretty wide spread, so this is going to be a good one.

And this loops back to “what do you mean by best”? From a recommendation perspective, I’m not sure what value a list has that includes Star Wars and doesn’t include Radiers of the Lost Ark, and ditto 2001 and, say, The Seventh Seal. But, okay, we’re doing a big-tent, anything possibly science fiction, in addition to pulling from much deeper into the back catalog than you usually see in a list like this. Theres a bunch of really weird movies on here that you don’t usually see on best-of lists, but I was glad to see them! There’s no bad movies on there, but there are certainly some spicy ones you need to be in the right headspace for.

These are all good things, to be clear! But the result is a deeply strange list.

The top 20 or so are the movies you expect, and the order feels almost custom designed to get the most links on twitter. But it’s the bottom half of the list that’s funny.

Is Repo Man better than Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure? Is Colossus: The Forbin Project better than Time Bandits? Are both of those better than The Fifth Element? Is Them better than Tron? Is Zardoz better than David Lynch’s Dune? I don’t know! (Especially that last one.) I think the answer to all of those is “no”, but I can imagine a guy who doesn’t think so? I’ve been cracking up at the mental image of a group of friends wanting to watch Jurassic Park, and theres the one guy who says “you want to watch the good Crichton movie? Check this out!” and drops Westworld on them.

You can randomly scroll to almost anywhere and compare two movies, and go “yeah, that sounds about right”, and then go about ten places in either direction and compare that movie to those first two and go “wait, what?”

And look, we know how these kinds of lists get written: you get a group of people together, and they bring with them movies they actually like, movies they want people to think they like, and how hipster contrarian they’re feeling, and that all gets mashed up into something that’ll drive “engagement”, and maybe generate some value for the shareholders.

But what I think is funny about these kinds of lists in general, and this list specifically, is imagining the implied author. Imagine this really was one guy’s personal ranking of science fiction movies. The list is still deranged, but in a delightful way, sort of a “hell yeah, man, you keep being you!”

It’s less of a list of best movies, and more your weirdest friend’s Id out on display. I kind of love it! The more I scrolled, I kept thinking “I don’t think I agree with this guy about anything, but I’m pretty sure we’d be friends.”

Time Zones Are Hard

In honor of leap day, my favorite story about working with computerized dates and times.

A few lifetimes ago, I was working on a team that was developing a wearable. It tracked various telemetry about the wearer, including steps. As you might imagine, there was an option to set a Step Goal for the day, and there was a reward the user got for hitting the goal.

Skipping a lot of details, we put together a prototype to do a limited alpha test, a couple hundred folks out in the real world walking around. For reasons that aren’t worth going into, and are probably still under NDA, we had to do this very quickly; on the software side we basically had to start from scratch and have a fully working stack in 2 or 3 months, for a feature set that was probably at minimum 6-9 months worth of work.

There were a couple of ways to slice what we meant by “day”, but we went with the most obvious one, midnight to midnight. Meaning that the user had until midnight to hit your goal, and then at 12:00 your steps for the day resets to 0.

Dates and Times are notoriously difficult for computers. Partly, this is because Dates and Times are legitimately complex. Look at the a full date: “February 29th 2024, 11:00:00 am”. Every value there has a different base, a different set of legal values. Month lengths, 24 vs 12 hour times, leap years, leap seconds. It’s a big tangle of arbitrary rules. If you take a date and time, and want to add 1000 minutes to it, the value of the result is “it depends”. This gets even worse when you add time zones, and the time zone’s angry sibling, daylight saving time. Now, the result of adding two times together also depends on where you were when it happened. It’s gross!

But the other reason it’s hard to use dates and times in computers is that they look easy. Everyone does this every day! How hard can it be?? So developers, especially developers working on platforms or frameworks, tend to write new time handling systems from scratch. This is where I link to this internet classic: Falsehoods programmers believe about time.

The upshot of all that is that there’s no good standard way to represent or transmit time data between systems, the way there is with, say, floating point numbers, or even unicode multi-language strings. It’s a stubbornly unsolved problem. Java, for example, has three different separate systems for representing dates and times built in to the language, none of which solve the whole problem. They’re all terrible, but in different ways.

Which brings me back to my story. This was a prototype, built fast. We aggressively cut features, anything that wasn’t absolutely critical went by the wayside. One of the things we cut out was Time Zone Support, and chose to run the whole thing in Pacific Time. We were talking about a test that was going to run about three months, which didn’t cross a DST boundary, and 95% of the testers were on the west coast. There were a handful of folks on the east cost, but, okay, they could handle their “day” starting and ending at 3am. Not perfect, but made things a whole lot simpler. They can handle a reset-to-zero at 3 am, sure.

We get ready to ship, to light to test run up.

“Great news!” someone says. “The CEO is really excited about this, he wants to be in the test cohort!”

Yeah, that’s great! There’s “executive sponsorship”, and then there’s “the CEO is wearing the device in meetings”. Have him come on down, we’ll get him set up with a unit.

“Just one thing,” gets causally mentioned days later, “this probably isn’t an issue, but he’s going to be taking them on his big publicized walking trip to Spain.”

Spain? Yeah, Spain. Turns out he’s doing this big charity walk thing with a whole bunch of other exec types across Spain, wants to use our gizmo, and at the end of the day show off that he’s hit his step count.

Midnight in California is 9am in Spain. This guy gets up early. Starts walking early. His steps are going to reset to zero every day somewhere around second breakfast.

Oh Shit.

I’m not sure we even said anything else in that meeting, we all just stood without a word, acquired a concerning amount of Mountain Dew, and proceeded to spend the next week and change hacking in time zone support to the whole stack: various servers, database, both iOS and Android mobile apps.

It was the worst code I have ever written, and of course it was so much harder to hack in after the fact in a sidecar instead of building it in from day one. But the big boss got hit step count reward at the end of the day every day, instead of just after breakfast.

From that point on, whenever something was described as hard, the immediate question was “well, is this just hard, or is it ’time zone’ hard?”

Today in Star Wars Links

Time marches on, and it turns out Episode I is turning 25 this year. As previously mentioned, the prequels have aged interestingly, and Episode I the most. It’s not any better than it used to be, but the landscape around it has changed enough that they don’t look quite like they used to. They’re bad in a way that no other movies were before or have been since, and it’s easier to see that now than it was at the time. As such, I very much enjoyed Matt Zoller Seitz’s I Used to Hate The Phantom Menace, but I Didn’t Know How Good I Had It :

Watching “The Phantom Menace,” you knew you were watching a movie made by somebody in complete command of their craft, operating with absolute confidence, as well as the ability to make precisely the movie they wanted to make and overrule anyone who objected. […] But despite the absolute freedom with which it was devised, “The Phantom Menace” seemed lifeless somehow. A bricked phone. See it from across the room, you’d think that it was functional. Up close, a paperweight.

[…]

Like everything else that has ever been created, films are products of the age in which they were made, a factor that’s neither here nor there in terms of evaluating quality or importance. But I do think the prequels have a density and exactness that becomes more impressive the deeper we get into the current era of Hollywood, wherein it is not the director or producer or movie star who controls the production of a movie, or even an individual studio, but a global megacorporation, one that is increasingly concerned with branding than art.

My drafts folder is full of still-brewing star wars content, but for the moment I’ll say I largely vibe with this? Episode I was not a good movie, but whatever else you can say about it, it was the exact movie one guy wanted to make, and that’s an increasingly rare thing. There have been plenty of dramatically worse movies and shows in the years sense, and they don’t even have the virtue of being one artist’s insane vision. I mean, jeeze, I’ll happily watch TPM without complaint before I watch The Falcon & The Winter Soldier or Iron Fist or Thor 2 again.

And, loosely related, I also very much enjoyed this interview with prequel-star Natalie Portman:

Natalie Portman on Striking the Balance Between Public and Private Lives | Vanity Fair

Especially this part:

The striking thing has been the decline of film as a primary form of entertainment. It feels much more niche now. If you ask someone my kids’ age about movie stars, they don’t know anyone compared to YouTube stars, or whatever.

There’s a liberation to it, in having your art not be a popular art. You can really explore what’s interesting to you. It becomes much more about passion than about commerce. And interesting, too, to beware of it becoming something elitist. I think all of these art forms, when they become less popularized, you have to start being like, okay, who are we making this for anymore? And then amazing, too, because there’s also been this democratization of creativity, where gatekeepers have been demoted and everyone can make things and incredible talents come up. And the accessibility is incredible. If you lived in a small town, you might not have been able to access great art cinema when I was growing up. Now it feels like if you’ve got an internet connection, you can get access to anything. It’s pretty wild that you also feel like at the same time, more people than ever might see your weird art film because of his extraordinary access. So it’s this two-sided coin.

I think this is the first time that I’ve seen someone admit that not only is 2019 is never going to happen again, but that’s a thing to embrace, not fear.

That Gum You Like Is Going To Come Back In Style

“Diane, 11:30 AM, February 24th. Entering the town of Twin Peaks.”

Zoozve

This is great. Radiolab cohost Latif Nasser notices that the solar system poster in his kid’s room has a moon for Venus—which doesn’t have a moon—and starts digging. It’s an extremely NPR (complimentary) slow burn solving of the simple mystery of what this thing on the poster was, with a surprisingly fun ending! Plus: “Quasi-moons!”

Space.com has a recap of the whole thing with links: Zoozve — the strange 'moon' of Venus that earned its name by accident. (See also: 524522 Zoozve - Wikipedia.)

One of the major recurring themes on Icecano are STEM people who need to take more humanties classes, but this is a case where the opposite is true?

Playthings For The Alone

Previously on Icecano: Space Glasses, Apple Vision Pro: New Ways to be Alone.

I hurt my back at the beginning of January. (Wait! This isn’t about to become a recipe blog, or worse, a late-90s AICN movie review. This is gonna connect, bare with me.) I did some extremely unwise “lift with your back, not your knees” while trying to get our neutronium-forged artificial Christmas tree out of the house. As usual for this kind of injury, that wasn’t the problem, the problem was when I got overconfident while full of ibuprofen and hurt it asecond time at the end of January. I’m much improved now, but that’s the one that really messed me up. I have this back brace thing that helps a lot—my son has nicknamed it The Battle Harness, and yeah, if there was a He-Man character that was also a middle-aged programmer, that’s what I look like these days. This is one of those injuries where what positions are currently comfortable is an ever-changing landscape, but the consistant element has been that none of them allow me to use a screen and a keyboard at the same time. (A glace back at the Icecano archives since the start of the year will provided a fairly accurate summary of how my back was doing.)

One of the many results of this is that I’ve been reading way, way more reviews of the Apple Cyber Goggles than I was intending to. I’ve very much been enjoying the early reactions and reviews of the Apple Cyber Goggles, and the part I enjoy the most has been that I no longer need to have a professional opinion about them.

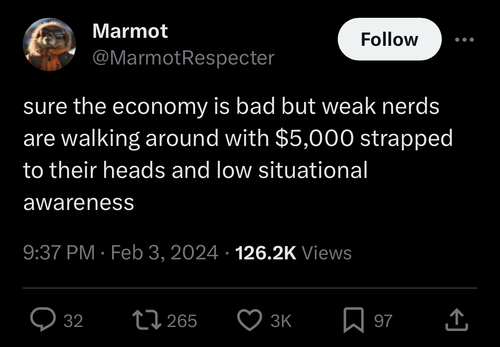

That’s a lie, actually my favorite part has been that as near as I can tell everyone seems to have individually invented “guy driving a cybertruck wearing vision pro”, which if I were Apple I’d treat as a 5-alarm PR emergency. Is anyone wearing these outside for any reason other than Making Content? I suspect not. Yet, anyway. Is this the first new Apple product that “normal people” immediately treated as being douchebag techbro trash? I mean, usually it gets dismissed as overly expensive hipster gear, but this feels different, somehow. Ed Zitron has a solid take on why: How Tech Outstayed Its Welcome.

Like jetpacks and hover cars before it, computers replacing screens with goggles is something science fiction decided was Going To Happen(tm). There’s a sense of inevitability about it, in the future we’re all going to use ski goggles to look at our email. If I was feeling better I’d go scare up some clips, but we’re all picturing the same things: Johnny Mnemonic, any cover art for any William Gibson book, that one Michael Douglas / Demi Moore movie, even that one episode of Murder She Wrote where Mrs. Potts puts on a Nintendo Power Glove and hacks into the Matrix.

(Also, personal sidebar: something I learned about myself the last couple of weeks is somehow I’ve led a life where in my mid-40s I can type “mnemonic” perfectly the first time every time, and literally can never write “johnny” without making a typo.)

But I picked jetpacks and hover cars on purpose—this isn’t something like Fusion Power that everyone also expects but stubbornly stays fifty years into the future, this is something that keeps showing up and turning out to not actually be a good idea. Jetpacks, it turns out, are kinda garbage in most cases? Computers, but for your face, was a concept science fiction latched on to long before anyone writing in the field had used a computer for much, and the idea never left. And people kept trying to build them! I used to work with a guy who literally helped build a prototype face-mounted PC during the Reagan administration, and he was far from the first person to work on it. Heck, I tried out a prototype VR headset in the early 90s. But the reality on the ground is that what we actually use computers for tends to be a bad fit for big glasses.

I have a very clear memory of watching J. Mnemonic the first time with an uncle who was probably the biggest science fiction fan of all time. The first scene where Mr. Mnemonic logs into cyberspace, and the screen goes all stargate as he puts on his ski goggles and flies into the best computer graphics that a mid-budget 1995 movie can muster, I remember my uncle, in full delight and without irony, yelling “that’s how you make a phone call!” He’d have ordered one of these on day one. But you know what’s kinda great about my actual video phone I have in my pocket he didn’t live to see? It just connects to the person I’m calling instead of making me fly around the opening credits of Tron first.

Partly because it’s such a long-established signifier of the future, and lots of various bits of science fiction have made them look very cool, there’s a deep, built-up reservoir of optimism and good will about the basic concept, despite many of the implementations being not-so-great. And because people keep taking swings at it, like jetpacks, face-mounted displays have carved out a niche where they excel. (VR; games mostly, for jetpacks: the opening of James Bond movies.)

And those niches have gotten pretty good! Just to be clear: Superhot VR is one of my favorite games of all time. I do, in fact, own an Oculus from back when they still used that name, and there’s maybe a half-dozen games where the head-mounted full-immersion genuinely results in a different & better experience than playing on a big screen.

And I think this has been one of the fundamental tensions around this entire space for the last 40 years: there’s a narrow band of applications where they’re clearly a good idea, but science fiction promised that these are the final form. Everyone wants to join up with Case and go ride with the other Console Jockeys. Someday, this will be the default, not just the fancy thing that mostly lives in the cabinet.

The Cyber Goggles keep making me thing about the Magic Leap. Remember them? Let me tell you a story. For those of you who have been living your lives right, Magic Leap is a startup who’ve been working on “AR goggles” for some time now. Back when I had to care about this professionally, we had one.

The Leap itself, was pair of thick goggles. I think there was a belt pack with a cable? I can’t quite remember now. The lenses were circular and mostly clear. It had a real steampunk dwarf quality, minus the decorative gears. The central feature was that the lenses were clear, but had an embedded transparent display, so the virtual elements would overlay with real life. It was heavy, heavier than you wanted it to be, and the lenses had the quality of looking through a pair of very dirty glasses, or walking out of a 3D movie without giving the eyewear back. You could see, but you could tell the lenses were there. But it worked! It did a legitimately amazing job of drawing computer-generated images over the real world, and they really looked like they were there, and then you could dismiss them, and you were back to looking at the office through Thorin’s welding goggles.

What was it actually do though? It clearly wasn’t sure. This was shortly after google glass, and it had a similar approach to being a stand-along device running “cut down” apps. Two of them have stuck in my memory.

The first was literally Angy Birds. But it projected the level onto the floor of the room you were in, blocks and pigs and all, so you could walk around it like it was a set of discarded kids toys. Was it better than “regular” angry birds? No, absolutely not, but it was a cool demo. The illusion was nearly perfect, the scattered blocks really stayed in the same place.

The second was the generic productivity apps. Email, calendar, some other stuff. I think there was a generic web browser? It’s been a while. They lived in these virtual screens, rectangles hanging in air. You could position them in space, and they’d stay there. I took a whole set of these screens and arrayed them in the air about and around my desk. I had three monitors in real life, and then another five or six virtual ones, each of the virtual ones showing one app. I could glance up, and see a whole array of summary information. The resolution was too low to use them for real work, and the lenses themselves were too cloudy to use my actual computer while wearing them.

You can guess the big problem though: I coudn’t show them to anybody. Anything I needed to share with a coworker needed to be on one of the real screens, not the virtual ones. Theres nothing quite so isolating as being able to see things no one else can see.

That’s stuck with me all these years. Those virtual screens surrounding my desk. That felt like something. Now, Magic Leap was clearly not the company to deliver a full version of that, even then it was clear they weren’t the ones to make a real go of the idea. But like I said, it stuck with me. Flash forward, and Apple goes and makes that one of the signature features of their cyber goggles.

I can’t ever remember a set of reviews for a new product that were trying this hard to get past the shortcomings and like the thing they were imagining. I feel like most reviews of this thing can be replaced with a clip from that one Simpson’s episode where Homer buys the first hover car, but it sucks, and Bart yells over the wind “Why’d you buy the first hover car ever made?”, to which Homer gleefully responds with “I know! It’s a hover car!” as the car rattles along, bouncing off the ground.

It’s clear what everyone suspected back over the summer is true; this isn’t the “real” product, this is a sketch, a prototype, a test article that Tim Apple is charging 4 grand to test. And, good for him, honestly. The “real” Apple Vision is probably rev 3 or 4, coming in 2028 or thereabouts.

I’m stashing the links to all the interesting ones I read here, mostly so I can find them again. (I apologize to those of you to whom this is a high-interest open tabs balance transfer.)

- Apple Vision Pro review: magic, until it’s not - The Verge

- Apple Vision Pro Review: The Best Headset Yet Is Just a Glimpse of the Future - WSJ

- Daring Fireball: The Vision Pro

- The Apple Vision Pro: A Review

- Michael Tsai - Blog - Apple Vision Pro Reviews

- Apple Vision Pro hands-on, again, for the first time - The Verge

- Hypercritical: Spatial Computing

- Manton Reece - Apple needs a flop

- Why Tim Cook Is Going All In on the Apple Vision Pro | Vanity Fair

- The Apple Vision Pro Is Spectacular and Sad - The Atlantic

- Daring Fireball: Simple Tricks and Nonsense

- All My Thoughts After 40 Hours in the Vision Pro — Wait But Why

But my favorite summary was from Today in Tabs The Business Section:

This is all a lot to read and gadget reviews are very boring so my summary is: the PDF Goggles aren’t a product but an expensive placeholder for a different future product that will hypothetically provide augmented reality in a way that people will want to use, which isn’t this way. If you want to spend four thousand dollars on this placeholder you definitely already know that, and you don’t need a review to find out.

The reviews I thought were the most interesting were the ones from Thompson and Zitron; They didn’t get review units, they bought them with their own money and with very specific goals of what they wanted to use them for, which then slammed into the reality of what the device actually can do:

Both of those guys really, really wanted to use their cyber goggles as a primary productivity tool, and just couldn’t. It’s not unlike the people who tried really hard to make their iPad their primary computer—you know who you are; hey man, how ya doing?—it’s possible, but barely.

There’s a definite set of themes across all that:

- The outward facing “eyesight” is not so great

- The synthetic faces for video calls as just as uncanny valley weird as we thought

- Watching movies is really, really cool—everyone really seems to linger on this one

- Big virtual screens for anything other than movies and other work seems mixed

- But why is this, though? “What’s the problem this is solving?”

Apple, I think at this point, has earned the benefit of the doubt when they launch new things, but I’ve spent the last week reading this going, “so that’s it, huh?” Because okay, it’s the thing from last summer. There’s no big “aha, this is why they made this”.

There’s a line from the first Verge hands-on, before the full review, where the author says:

I know what I saw, but I’m still trying to figure out where this headset fits in real life.

Ooh, ooh, pick me! I know! It’s a Plaything For The Alone.

They know—they know—that headsets like this are weird and isolating, but seem to have decided to just shrug, accept that as the cost of doing business. As much as they pay lip service to being able to dial into the real world, this is more about dialing out, about tuning out the world, about having an experience only you can have. They might not be by themselves, but they’re Alone.

A set of sci-fi sketches as placeholders for features, entertaining people who don’t have anyone to talk to.

My parents were over for the Super Bowl last weekend. Sports keep being cited as a key feature for the cyber goggles, cool angles, like you’re really there. I’ve never in my life watched sports by myself. Is the idea that everyone will have their own goggles for big games? My parents come over with their own his-and-hers headsets, we all sit around with these things strapped to our faces and pass snacks around? Really? There’s no on-court angle thats better than gesturing wildly at my mom on the couch next to me.

How alone do you have to be to even think of this?

With all that said, what’s this thing for? Not the future version, not the science fiction hallucination, this thing you can go out and buy today? A Plaything for the Alone, sure, but to what end?

The consistent theme I noticed, across nearly every article I read, was that just about everyone stops and mentions that thing where you can sit on top of mount hood and watch a movie by yourself.

Which brings me back around to my back injury. I’ve spent the last month-and-change in a variety of mostly inclined positions. There’s basically nowhere to put a screen or a book that’s convenient for where my head needs to be, so in addition to living on ibuprofen, I’ve been bored out of my mind.

And so for a second, I got it. I’m wedged into the couch, looking at the TV at a weird angle, and, you know what? Having a screen strapped to my face that just oriented to where I could look instead of where I wanted to look sounded pretty good. Now that you mention it, I could go for a few minutes on top of Mount Hood.

All things considered, as back injuries go, I had a pretty mild one. I’ll be back to normal in a couple of weeks, no lasting damage, didn’t need professional medical care. But being in pain/discomfort all day is exhausting. I ended up taking several days off work, mostly because I was just to tired to think or talk to anyone. There’d be days where I was done before sundown; not that I didn’t enjoy hanging out with my kids when they got home from school, but I just didn’t have any gas left in the tank to, you know, say anything. I was never by myself, but I frequently needed to be alone.

And look, I’m lucky enough that when I needed to just go feel sorry for myself by myself, I could just go upstairs. And not everyone has that. Not everyone has something making them exhausted that gets better after a couple of weeks.

The question every one keeps asking is “what problem are these solving?”

Ummm, is the problem cities?

When they announced this thing last summer, I thought the visual of a lady in the cramped IKEA demo apartment pretending to be out on a mountain was a real cyberpunk dystopia moment, life in the burbclaves got ya down? CyberGoggles to the rescue. But every office I ever worked in—both cube farms and open-office bullpens—was full of people wearing headphones. Trying to blot out the noise, literal and figurative, of the environment around them and focus on something. Or just be.

Are these headphones for the eyes?

Maybe I’ve been putting the emphasis in the wrong place. They’re a Plaything for the Alone, but not for those who are by themselves, but for those who wish they could be.