Fractals

(This may not appear correctly inside a feed reader or other limited-formatting browser.)

Part 1: DFW

- Let me tell you a story about something that happens to me. Maybe it happens to you?

- This same thing has happened probably a dozen times, if not more, over the last couple of decades. I’ll be in a group some kind, where the membership is not entirely optional—classmates, coworkers, other parents at the kid’s school—and the most irritating, obnoxious member of the group, the one I have the least in common with and would be the least likely to spend time with outside of whatever it is we’re doing, will turn to me, face brightening, and say “Hey! I bet you’re a huge fan of David Foster Wallace.”

- I’ve learned that the correct answer to this is a succinct “you know, he didn’t invent footnotes.”A

- Because reader, they do not bet correctly. To be very clear: I have never1 read any of his work. I’m aware he exists, and there was that stretch in the late 90s where an unread copy of Infinite Jest seemed to spontaneously materialize on everyone’s shelves. But I don’t have an opinion on the guy?2

- I have to admit another reaction, in that in addition to this behavior, most of the people41 you run in to that actually recommend his work are deeply obnoxious.α

- So, I’ve never been able to shake the sense that this is somehow meant as an insult. There’s a vague “attempted othering” about it; it's never presented as “I liked this and I bet you will too,” or “Aha, I finally found a thing we have in common!” it’s more of “Oh, I bet you’re one of those people”. It’s the snap of satisfaction that gets to me. The smug air of “oh, I’ve figured you out.”

- And look, I’m a late-era Gen-X computer nerd programmer—there are plenty of stereotypes I’ll own up to happily. Star Wars fan? Absolutely. The other 80s nerd signifiers? Trek, Hitchhiker’s Guide, Monty Python? Sure, yep, yep. Doctor Who used to be the outlier, but not so much anymore.3 William Gibson, Hemmingway, Asimov? For sure.

- But this one I don’t understand. Because it cant just be footnotes, right?

- I bring all this up because Patricia Lockwood4 has written a truly excellent piece on DFW: [Where be your jibes now?].7 It’s phenomenal, go read it!

- But, I suspect I read it with a unique viewpoint. I devoured it with one question: “am I right to keep being vaguely insulted?”

- And, he nervously laughed, I still don’t know!

- She certainly seems to respect him, but not actually like him very much? I can’t tell! It’s evocative, but ambiguous? It’s nominally a review of his last, unfinished, posthumously published book, but then works its way though his strange and, shall we say, “complicated” reputation, and then his an overview of the rest of his work.

- And I have the same reaction I did every time I hear about his stuff, which is some combination of “that guy sounds like he has problems” (he did) and “that book sounds awful” (they do).

- “I bet you’re a fan”

- Why? Why do you bet that?

- I’m self-aware enough to know that the correct response to all this is probably just to [link to this onion article] And I guess there’s one way to know.

- But look. I’m just not going to read a million pages to find out.

Part 2: Footnotes, Hypertext, and Webs

- Inevitably, this is after I’ve written something full of footnotes.B

- Well, to expand on that, this usually happens right after I write something with a joke buried in a footnote. I think footnotes are funny! Or rather, I think they’re incredibly not funny by default, a signifier of a particular flavor of dull academic writing, which means any joke you stash in one becomes automatically funnier by virtue of surprise.C

- I do like footnotes, but what I really like is hypertext. I like the way hypertext can spider-web out, spreading in all directions. Any text always has asides, backstory, details, extending fractally out. There’s always more to say about everything. Real life, even the simple parts, doesn’t fit into neat linear narratives. Side characters have full lives, things got where they are somehow, everything has an explanation, a backstory, more details, context. So, generally writing is as much the art of figuring out what to leave out as anything. But hypertext gives you a way to fit all those pieces together, to write in a way that’s multidimensional.D

- Fractals. There’s always more detail. Another story. “On that subject…”E

- Before we could [link] to things, the way to express that was footnotes. Even here, on the system literally called “the web”, footnotes still work as a coherent technique for wrangling hypertext into something easier to get your arms around.F

- But the traditional hypertext [link] is focused on detail—to find out more, click here! The endless cans of rabbit holes of wikipedia’s links to other articles. A world where every noun has a blue underline leading to another article, and another, and so on.G

- Footnotes can do that, but they have another use that links don’t—they can provide commentary.13 A well deployed footnote isn’t just “click here to read more”, it’s a commentary, annotations, a Gemara.H

- I come by my fascination with footnotes honestly: The first place I ever saw footnotes deployed in an interesting way was, of all things, a paper in a best-of collection of the Journal of Irreproducible Results.9 Someone submitted a paper that was only a half-sentence long and then had several pages of footnotes that contained the whole paper, nested in on itself.12 I loved this. It was like a whole new structure opened up that had been right under my nose the whole time.J

- Although, if I’m honest, the actual origin of my love of footnotes is probably reading too many choose your own adventure books.17

- I am also a huge fan of overly-formalist structural bullshit, obviously.α

Part 3: Art from Obnoxious People

- What do you do with art that’s recommended by obnoxious people?40

- In some ways, this is not totally unlike how to deal with art made by “problematic” artists; where if we entirely restricted our intake to art made exclusively by good people, we’d have Mister Rogers' Neighborhood and not much else. But maintaining an increasingly difficult cognitive dissonance while watching Annie Hall is one thing, but when someone you don’t like recommends something?38

- To be fair, or as fair as possible, most of this has very, very little to do with the art itself. Why has a movie about space wizards overthrowing space fascists become the favorite movie of actual earth fascists? Who knows? The universe is strange. It’s usually not healthy to judge art by its worst fans.36

- Usually.

- In my experience, art recommended by obnoxious people takes roughly three forms:32

- There’s art where normal people enjoy it, and it’s broadly popular, and then there’s a deeply irritating toxic substrate of people who maybe like it just a little too much to be healthy. 30

- Star Trek is sort of the classic example here, or Star Wars, or Monty Python, or, you know, all of sports. Things that are popular enough where there’s a group of people who have tried to paper over a lack personality by memorizing lines from a 70s BBC sketch comedy show, or batter’s statistics from before they were born. 28

- Then there’s the sort of art that unlocks a puzzle, where, say, you have a coworker who is deeply annoying for reasons you can’t quite put your finger on, and then you find out their favorite book is Atlas Shrugged. A weight lifts, aha, you say, got it. It all makes sense now. 26

- And then, there’s art24 that exclusively comes into your life from complete dipshits.

- The trick is figuring out which one you're dealing with.q

Part 4: Endnotes

- What never? Well, hardly ever!

- I think I read the thing where he was rude about cruises?

- And boy, as an aside, “I bet you’re a Doctor Who fan” has meant at least four distinct things since I started watching Tom Baker on PBS in the early 80s.

- Who5 presumably got early parole from her thousand years of jail.6

- In the rough draft of this I wrote “Patricia Highsmith,” and boy would that be a whole different thing!

- Jail for mother!

- In the spirit of full disclosure, she wrote it back in July, whereupon I saved it to Instapaper and didn’t read it until this week. I may not be totally on top of my list of things to read?35

- "Notes Towards a Mental Breakdown" (1967)

- The JoIR is a forum for papers that look and move like scientific papers, but are also a joke.

- The bartender is a die-hard Radiers fan; he happily launches into a diatribe about what a disaster the Las Vegas move has been, but that F1 race was pretty great. A few drinks in, he wants to tell you about his “radical” art installation in the back room? To go look, turn to footnote ω To excuse yourself, turn to footnote 20

- I knew a girl in college whose ex-boyfriend described Basic Instinct as his favorite movie, and let me tell you, every assumption you just made about that guy is true.

- Although, in fairness, that JoIR paper was probably directly inspired by that one J. G. Ballard story.8

- This was absurdly hard21 to put together.39

- The elf pulls his hood back and asks: “Well met, traveller! What was your opinion of the book I loaned you?” He slides a copy of Brief Interviews with Hideous Men across the table. To have no opinion, turn to footnote d. To endorse it enthusiastically, turn to footnote α

- Or is it five?

- You’re right, that bar was sus. Good call, adventurer! To head further into town, turn to footnote 20. To head back out into the spooky woods, go to footnote 22.

- You stand in the doorway of a dark and mysterious tavern. Miscreants and desperadoes of all description fill the smoky, shadowed room. You’re looking for work. Your sword seems heavier than normal at your side as you step into the room. If you... Talk to the bartender, turn to footnote 10. Talk to the hooded Elf in the back corner, turn to footnote 14. To see what’s going on back outside, turn to footnote 16.

- "Glass Onion” from The Beatles, aka The White Album

- Superscript and anchor tags for the link out, then an ordered list where each List Item has to have a unique id so that those anchor tags can link back to them.23

- You head into town. You find a decent desk job; you only mean to work there for a bit, but it’s comfortable and not that hard, so you stay. Years pass, and your sword grows dusty in the back room. You buy a minivan! You get promoted to Director of Internal Operations, which you can never describe correctly to anyone. Then, the market takes a downturn, and you’re one of the people who get “right sized”. They offer you a generous early retirement. To take it, turn to footnote 25. To decline, turn to footnote 22.

- But did you know that HTML doesn’t have actual support33 for footnotes?23

-

You journey into the woods. You travel far, journeying across the blasted plains of Hawksroost, the isles of Ka’ah’wan-ah, you climb the spires of the Howling Mountains, you delve far below the labyrinth of the Obsidian Citadel; you finally arrive at the domain of the Clockwork Lord, oldest of all things. Its ancient faces turns towards you, you may ask a boon.

“Is this all there is? Is there nothing more?”: Footnote 27

“I wish for comfort and wealth!” Footnote 25

- I have no idea how this will look in most browsers.31

- This usually still isn’t a direct comment on the art itself, but on the other hand, healthy people don’t breathlessly rave about Basic Instinct,11 you know?

-

Good call! You settle into a comfortable retirement in the suburbs. Your kids grow up, move out, grow old themselves. The years tick by. One day, when the grandkids are over, one of them finds your old sword in the garage. You gingerly pick it up, dislodging generations of cobwebs. You look down, and see old hands holding it, as if for the first time. You don’t answer when one of them asks what it is; you just look out the window. You can’t see the forest anymore, not since that last development went in. You stand there a long time.

*** You have died ***

- And turnabout is fair play: I’ve watched people have this a-ha moment with me and Doctor Who.

-

The Clockwork Lord has no expression you can understand, but you know it is smiling. “There is always more,” it says, in infinite kindness. “The door to the left leads to the details you are seeking. The door to the right has the answer you are lacking. You may choose.”

Left: Footnote a

Right: Footnote 29

- Other examples of this category off the top of my head: Catcher in the rye, MASH, all of Shakespeare.

-

You step through the doorway, and find yourself in an unfamiliar house. There are people there, people you do not know. With a flash of insight, you realize the adult is your grandchild, far past the time you knew them, the children are your great-grandchildren, whom you have never met. You realize that you are dead, and have been for many years. All your works have been forgotten, adventures, jobs, struggles, lost as one more grain of sand on the shore of time. Your grandchild, now old themselves, is telling their child a story—a story about you. A minor thing, a trifle, something silly you did at a birthday party once. You had totally forgotten, but the old face of the 6-year old who’s party it was didn’t. They’re telling a story.

Oh. You see it,

*** You Have Ascended ***

- Fanatics, to coin a phrase?

- This feels like it should have one of those old “works best in Netscape Navigator”, except Netscape would choke on all this CSS.37

-

Björk: (over the phone) I have to say I'm a great fan of triangles.

Space Ghost: Well, I have to say that I am a great fan of Chuck Norris, and he was in the Delta Force, and the delta was a triangle.

- Instead you have to code19 them by hand.

- Yeah, I see what you did there.

- Okay, that's also a lie; I've actually been working on this on-and-off since July.13

- Cases in point: I, II, III , IIII

- Certified: “It works on my machine!”α

- Especially when they themselves don’t seem to like it?

- I mean, the writing itself was tricky enough, with three15 interleaving essays.

- Not annoying people, not assholes: obnoxious. Hard to define, but like pornography, you know it when you see it.

- On the other hand, back in the 90s these people were asking about Robert Anton Wilson or saying “fnord” at me, so some things have gotten better, I guess.

- That's not the problem. This is: Change. Read it through again and you'll get it.

Part 5: No Moral.

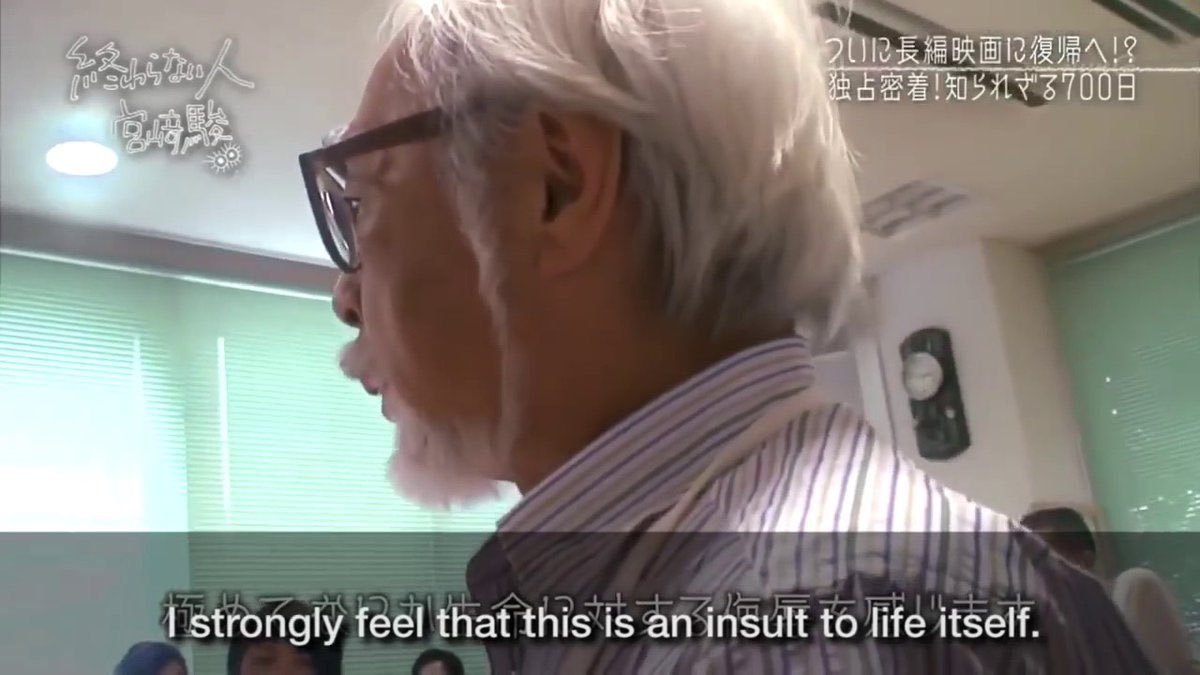

Fully Automated Insults to Life Itself

In 20 years time, we’re going to be talking about “generative AI”, in the same tone of voice we currently use to talk about asbestos. A bad idea that initially seemed promising which ultimately caused far more harm than good, and that left a swathe of deeply embedded pollution across the landscape that we’re still cleaning up.

It’s the final apotheosis of three decades of valuing STEM over the Humanities, in parallel with the broader tech industry being gutted and replaced by a string of venture-backed pyramid schemes, casinos, and outright cons.

The entire technology is utterly without value and needs to be scrapped, legislated out of existence, and the people involved need to be forcibly invited to find something better to send their time on. We’ve spent decades operating under the unspoken assumption that just because we can build something, that means it’s inevitable and we have to build it first before someone else does. It’s time to knock that off, and start asking better questions.

AI is the ultimate form of the joke about the restaurant where the food is terrible and also the portions are too small. The technology has two core problems, both of which are intractable:

- The output is terrible

- It’s deeply, fundamentally unethical

Probably the definite article on generative AI’s quality, or profound lack thereof, is Ted Chiang’s ChatGPT Is a Blurry JPEG of the Web; that’s almost a year old now, and everything that’s happened in 2023 has only underscored his points. Fundamentally, we’re not talking about vast cyber-intelligences, we’re talking Sparkling Autocorrect.

Let me provide a personal anecdote.

Earlier this year, a coworker of mine was working on some documentation, and had worked up a fairly detailed outline of what needed to be covered. As an experiment, he fed that outline into ChatGPT, intended to publish the output, and I offered to look over the result.

At first glance it was fine. Digging in, thought, it wasn’t great. It wasn’t terrible either—nothing in it was technically incorrect, but it had the quality of a high school book report written by someone who had only read the back cover. Or like documentation written by a tech writer who had a detailed outline they didn’t understand and a word count to hit? It repeated itself, it used far too many words to cover very little ground. It was, for lack of a better word, just kind of a “glurge”. Just room-temperature tepidarium generic garbage.

I started to jot down some editing notes, as you do, and found that I would stare at a sentence, then the whole paragraph, before crossing the paragraph out and writing “rephrase” in the margin. To try and be actually productive, I took a section and started to rewrite in what I thought was better, more concise manner—removing duplicates, omitting needless words. De-glurgifying.

Of course, I discovered I had essentially reconstituted the outline.

I called my friend back and found the most professional possible way to tell him he needed to scrap the whole thing start over.

It left me with a strange feeling, that we had this tool that could instantly generate a couple thousand words of worthless text that at first glance seemed to pass muster. Which is so, so much worse than something written by a junior tech writer who doesn’t understand the subject, because this was produced by something that you can’t talk to, you can’t coach, that will never learn.

On a pretty regular basis this year, someone would pop up and say something along the lines of “I didn’t know the answer, and the docs were bad, so I asked the robot and it wrote the code for me!” and then they would post some screenshots of ChatGPTs output full of a terribly wrong answer. Human’s AI pin demo was full of wrong answers, for heaven’s sake. And so we get this trend where ChatGPT manages to be an expert in things you know nothing about, but a moron about things you’re an expert in. I’m baffled by the responses to the GPT-n “search” “results”; they’re universally terrible and wrong.

And this is all baked in to the technology! It’s a very, very fancy set of pattern recognition based on a huge corpus of (mostly stolen?) text, computing the most probable next word, but not in any way considering if the answer might be correct. Because it has no way to, thats totally outside the bounds of what the system can achieve.

A year and a bit later, and the web is absolutely drowning in AI glurge. Clarkesworld had to suspend submissions for a while to get a handle on blocking the tide of AI garbage. Page after page of fake content with fake images, content no one ever wrote and only meant for other robots to read. Fake articles. Lists of things that don’t exist, recipes no one has ever cooked.

And we were already drowning in “AI” “machine learning” gludge, and it all sucks. The autocorrect on my phone got so bad when they went from the hard-coded list to the ML one that I had to turn it off. Google’s search results are terrible. The “we found this answer for you” thing at the top of the search results are terrible.

It’s bad, and bad by design, it can’t ever be more than a thoughtless mashup of material it pulled in. Or even worse, it’s not wrong so much as it’s all bullshit. Not outright lies, but vaguely truthy-shaped “content”, freely mixing copied facts with pure fiction, speech intended to persuade without regard for truth: Bullshit.

Every generated image would have been better and funnier if you gave the prompt to a real artist. But that would cost money—and that’s not even the problem, the problem is that would take time. Can’t we just have the computer kick something out now? Something that looks good enough from a distance? If I don’t count the fingers?

My question, though, is this: what future do these people want to live in? Is it really this? Swimming a sea of glurge? Just endless mechanized bullshit flooding every corner of the Web?Who looked at the state of the world here in the Twenties and thought “what the world needs right now is a way to generate Infinite Bullshit”?

Of course, the fact that the results are terrible-but-occasionally-fascinating obscure the deeper issue: It’s a massive plagiarism machine.

Thanks to copyleft and free & open source, the tech industry has a pretty comprehensive—if idiosyncratic—understanding of copyright, fair use, and licensing. But that’s the wrong model. This isn’t about “fair use” or “transformative works”, this is about Plagiarism.

This is a real “humanities and the liberal arts vs technology” moment, because STEM really has no concept of plagiarism. Copying and pasting from the web is a legit way to do your job.

(I mean, stop and think about that for a second. There’s no other industry on earth where copying other people’s work verbatim into your own is a widely accepted technique. We had a sign up a few jobs back that read “Expert level copy and paste from stack overflow” and people would point at it when other people had questions about how to solve a problem!)

We have this massive cultural disconnect that would be interesting or funny if it wasn’t causing so much ruin. This feels like nothing so much as the end result of valuing STEM over the Humanities and Liberal Arts in education for the last few decades. Maybe we should have made sure all those kids we told to “learn to code” also had some, you know, ethics? Maybe had read a couple of books written since they turned fourteen?

So we land in a place where a bunch of people convinced they’re the princes of the universe have sucked up everything written on the internet and built a giant machine for laundering plagiarism; regurgitating and shuffling the content they didn’t ask permission to use. There’s a whole end-state libertarian angle here too; just because it’s not explicitly illegal, that means it’s okay to do it, ethics or morals be damned.

“It’s fair use!” Then the hell with fair use. I’d hate to lose the wayback machine, but even that respects robots.txt.

I used to be a hard core open source, public domain, fair use guy, but then the worst people alive taught a bunch of if-statements to make unreadable counterfit Calvin & Hobbes comics, and now I’m ready to join the Butlerian Jihad.

Why should I bother reading something that no one bothered to write?

Why should I bother looking at a picure that no one could be bothered to draw?

Generative AI and it’s ilk are the final apotheosis of the people who started calling art “content”, and meant it.

These are people who think art or creativity are fundamentally a trick, a confidence game. They don’t believe or understand that art can be about something. They reject utter the concept of “about-ness”, the basic concept of “theme” is utterly beyond comprehension. The idea that art might contain anything other than its most surface qualities never crosses their mind. The sort of people who would say “Art should soothe, not distract”. Entirely about the surface aesthetic over anything.

(To put that another way, these are the same kind people who vote Republican but listen to Rage Against the Machine.)

Don’t respect or value creativity.

Don’t respect actual expertise.

Don’t understand why they can’t just have what someone else worked for. It’s even worse than wanting to pay for it, these creatures actually think they’re entitled to it for free because they know how to parse a JSON file. It feels like the final end-point of a certain flavor of free software thought: no one deserves to be paid for anything. A key cultual and conceptual point past “information wants to be free” and “everything is a remix”. Just a machine that endlessly spits out bad copies of other work.

They don’y understand that these are skills you can learn, you have to work at, become an expert in. Not one of these people who spend hours upon hours training models or crafting prompts ever considered using that time to learn how to draw. Because if someone else can do it, they should get access to that skill for free, with no compensation or even credit.

This is why those machine generated Calvin & Hobbes comics were such a shock last summer; anyone who had understood a single thing about Bill Watterson’s work would have understood that he’d be utterly opposed to something like that. It’s difficult to fathom someone who liked the strip enough to do the work to train up a model to generate new ones while still not understanding what it was about.

“Consent” doesn’t even come up. These are not people you should leave your drink uncovered around.

But then you combine all that with the fact that we have a whole industry of neo-philes, desperate to work on something New and Important, terrified their work might have no value.

(See also: the number of abandoned javascript frameworks that re-solve all the problems that have already been solved.)

As a result, tech has an ongoing issue with cool technology that’s a solution in search of a problem, but ultimately is only good for some kind of grift. The classical examples here are the blockchain, bitcoin, NFTs. But the list is endless: so-called “4th generation languages”, “rational rose”, the CueCat, basically anything that ever got put on the cover of Wired.

My go-to example is usually bittorrent, which seemed really exciting at first, but turned out to only be good at acquiring TV shows that hadn’t aired in the US yet. (As they say, “If you want to know how to use bittorrent, ask a Doctor Who fan.”)

And now generative AI.

There’s that scene at the end of Fargo, where Frances McDormand is scolding The Shoveler for “all this for such a tiny amount of money”, and thats how I keep thinking about the AI grift carnival. So much stupid collateral damage we’re gonna be cleaning up for years, and it’s not like any of them are going to get Fuck You(tm) rich. No one is buying an island or founding a university here, this is all so some tech bros can buy the deluxe package on their next SUV. At least crypto got some people rich, and was just those dorks milking each other; here we all gotta deal with the pollution.

But this feels weirdly personal in a way the dunning-krugerrands were not. How on earth did we end up in a place where we automated art, but not making fast food, or some other minimum wage, minimum respect job?

For a while I thought this was something along one of the asides in David Graeber’s Bullshit Jobs, where people with meaningless jobs hate it when other people have meaningful ones. The phenomenon of “If we have to work crappy jobs, we want to pull everyone down to our level, not pull everyone up”. See also: “waffle house workers shouldn’t make 25 bucks an hour”, “state workers should have to work like a dog for that pension”, etc.

But no, these are not people with “bullshit jobs”, these are upper-middle class, incredibly comfortable tech bros pulling down a half a million dollars a year. They just don’t believe creativity is real.

But because all that apparently isn’t fulfilling enough, they make up ghost stories about how their stochastic parrots are going to come alive and conquer the world, how we have to build good ones to fight the bad ones, but they can’t be stopped because it’s inevitable. Breathless article after article about whistleblowers worried about how dangerous it all is.

Just the self-declared best minds of our generation failing the mirror test over and over again.

This is usually where someone says something about how this isn’t a problem and we can all learn to be “prompt engineers”, or “advisors”. The people trying to become a prompt advisor are the same sort who would be proud they convinced Immortan Joe to strap them to the back of the car instead of the front.

This isn’t about computers, or technology, or “the future”, or the inevitability of change, or the march or progress. This is about what we value as a culture. What do we want?

“Thus did a handful of rapacious citizens come to control all that was worth controlling in America. Thus was the savage and stupid and entirely inappropriate and unnecessary and humorless American class system created. Honest, industrious, peaceful citizens were classed as bloodsuckers, if they asked to be paid a living wage. And they saw that praise was reserved henceforth for those who devised means of getting paid enormously for committing crimes against which no laws had been passed. Thus the American dream turned belly up, turned green, bobbed to the scummy surface of cupidity unlimited, filled with gas, went bang in the noonday sun.” ― Kurt Vonnegut, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater

At the start of the year, the dominant narrative was that AI was inevitable, this was how things are going, get on board or get left behind.

Thats… not quite how the year went?

AI was a centerpiece in both Hollywood strikes, and both the Writers and Actors basically ran the table, getting everything they asked for, and enshrining a set of protections from AI into a contract for the first time. Excuse me, not protection from AI, but protection from the sort of empty suits that would use it to undercut working writers and performers.

Publisher after publisher has been updating their guidelines to forbid AI art. A remarkable number of other places that support artists instituted guidlines to ban or curtail AI. Even Kickstarter, which plunged into the blockchain with both feet, seemed to have learned their lesson and rolled out some pretty stringent rules.

Oh! And there’s some actual high-powered lawsuits bearing down on the industry, not to mention investigations of, shall we say, “unsavory” material in the training sets?

The initial shine seems to be off, where last year was all about sharing goofy AI-generated garbage, there’s been a real shift in the air as everyone gets tired of it and starts pointing out that it sucks, actually. And that the people still boosting it all seem to have some kind of scam going. Oh, and in a lot of cases, it’s literally the same people who were hyping blockchain a year or two ago, and who seem to have found a new use for their warehouses full of GPUs.

One of the more heartening and interesting developments this year was the (long overdue) start of a re-evaluation of the Luddites. Despite the popular stereotype, they weren’t anti-technology, but anti-technology-being-used-to-disenfrancise-workers. This seems to be the year a lot of people sat up and said “hey, me too!”

AI isn’t the only reason “hot labor summer” rolled into “eternal labor september”, but it’s pretty high on the list.

Theres an argument thats sometimes made that we don’t have any way as a society to throw away a technology that already exists, but that’s not true. You can’t buy gasoline with lead in it, or hairspray with CFCs, and my late lamented McDLT vanished along with the Styrofoam that kept the hot side hot and the cold side cold.

And yes, asbestos made a bunch of people a lot of money and was very good at being children’s pyjamas that didn’t catch fire, as long as that child didn’t need to breathe as an adult.

But, we've never done that for software.

Back around the turn of the century, there was some argument around if cryptography software should be classified as a munition. The Feds wanted stronger export controls, and there was a contingent of technologists who thought, basically, “Hey, it might be neat if our compiler had first and second amendment protection”. Obviously, that didn’t happen. “You can’t regulate math! It’s free expression!”

I don’t have a fully developed argument on this, but I’ve never been able to shake the feeling like that was a mistake, that we all got conned while we thought we were winning.

Maybe some precedent for heavily “regulating math” would be really useful right about now.

Maybe we need to start making some.

There’s a persistant belief in computer science since computers were invented that brains are a really fancy powerful computer and if we can just figure out how to program them, intelligent robots are right around the corner.

Theres an analogy that floats around that says if the human mind is a bird, then AI will be a plane, flying, but very different application of the same principals.

The human mind is not a computer.

At best, AI is a paper airplane. Sometimes a very fancy one! With nice paper and stickers and tricky folds! Byt the key is that a hand has to throw it.

The act of a person looking at bunch of art and trying to build their own skills is fundamentally different than a software pattern recognition algorithm drawing a picture from pieces of other ones.

Anyone who claims otherwise has no concept of creativity other than as an abstract concept. The creative impulse is fundamental to the human condition. Everyone has it. In some people it’s repressed, or withered, or undeveloped, but it’s always there.

Back in the early days of the pandemic, people posted all these stories about the “crazy stuff they were making!” It wasn’t crazy, that was just the urge to create, it’s always there, and capitalism finally got quiet enough that you could hear it.

“Making Art” is what humans do. The rest of society is there so we stay alive long enough to do so. It’s not the part we need to automate away so we can spend more time delivering value to the shareholders.

AI isn’t going to turn into skynet and take over the world. There won’t be killer robots coming for your life, or your job, or your kids.

However, the sort of soulless goons who thought it was a good idea to computer automate “writing poetry” before “fixing plumbing” are absolutely coming to take away your job, turn you into a gig worker, replace whoever they can with a chatbot, keep all the money for themselves.

I can’t think of anything more profoundly evil than trying to automate creativity and leaving humans to do the grunt manual labor.

Fuck those people. And fuck everyone who ever enabled them.

It’ll Be Worth It

An early version of this got worked out in a sprawling Slack thread with some friends. Thanks helping me work out why my perfectly nice neighbor’s garage banner bugs me, fellas

There’s this house about a dozen doors down from mine. Friendly people, I don’t really know them, but my son went to school with their youngest kid, so we kinda know each other in passing. They frequently have the door to the garage open, and they have some home gym equipment, some tools, and a huge banner that reads in big block capital letters:

NOBODY CARES WORK HARDER

My reaction is always to recoil slightly. Really, nobody? Even at your own home, nobody? And I think “you need better friends, man. Maybe not everyone cares, but someone should.” I keep wanting to say “hey man, I care. Good job, keep it up!” It feels so toxic in a way I can’t quite put my finger on.

And, look, I get it. It’s a shorthand to communicate that we’re in a space where the goal is what matters, and the work is assumed. It’s very sports-oriented worldview, where the message is that the complaints don’t matter, only the results matter. But my reaction to things like that from coaches in a sports context was always kinda “well, if no one cares, can I go home?”

(Well, that, and I would always think “I’d love to see you come on over to my world and slam into a compiler error for 2 hours and then have me tell you ‘nobody cares, do better’ when you ask for help and see how you handle that. Because you would lose your mind”)

Because that’s the thing: if nobody cared, we woudn’t be here. We’re hever because we think everyone cares.

The actual message isn’t “nobody cares,” but:

“All this will be worth it in the end, you’ll see”

Now, that’s a banner I could get behind.

To come at it another way, there’s the goal and there’s the work. Depending on the context, people care about one or the other. I used to work with some people who would always put the number of hours spent on a project as the first slide of their final read-outs, and the rest of us used to make terrible fun of them. (As did the execs they were presenting to.)

And it’s not that the “seventeen million hours” wasn’t worth celebrating, or that we didn’t care about it, but that the slide touting it was in the wrong venue. Here, we’re in an environment where only care about the end goal. High fives for working hard go in a different meeting, you know?

But what really, really bugs me about that banner specifically, and things like it, that that they’re so fake. If you really didn’t think anyone cares, you wouldn’t hang a banner up where all your neighbors could see it over your weight set. If you really thought no one cared, you wouldn’t even own the exercise gear, you’d be inside doing something you want to do! Because no one has to hang a “WORK HARDER” banner over a Magic: The Gathering tournament, or a plant nursery, or a book club. But no, it’s there because you think everyone cares, and you want them to think you’re cool because you don’t have feelings. A banner like that is just performative; you hang something like that because you want others to care about you not caring.

There’s a thing where people try and hold up their lack of emotional support as a kind of badge of honor, and like, if you’re at home and really nobody cares, you gotta rethink your life. And if people do care, why do you find pretending they don’t motivating? What’s missing from your life such that pretending you’re on your own is better than embracing your support?

The older I get, the less tolerance I have for people who think empathy is some kind of weakness, that emotional isolation is some kind of strength. The only way any of us are going to get through any of this is together.

Work Harder.

Everyone Cares.

I’ll Be Worth It.

Books I read in 2022, part 3

(That I have mostly nice things to say about)

Programming note: while clearning out the drafts folder as I wind the year down, I discovered that much to my amusement and surprise I wrote most of the third post on the books I read last year, but somehow never posted it? One editing & expansion pass later, and here it is.

Previously , Previously .

Neil Gaiman's Chivalry, adapted by Colleen Duran

A perfect jewel of a book. The story is slight, but sweet. Duran’s art, however, is gorgeous, perfectly sliding between the style of an illuminated manuscript and watercolor paintings. A minor work by two very capable artists, but clearly a labor of love, and tremendous fun.

The Murderbot Diaries 1&2: All Systems Red and Artificial Condition by Martha Wells

As twitter started trending towards it’s final end last summer, I decided I’b better stary buying some of the books I’d been seeing people enthuse about. There was a stretch there where it seemed like my entire timeline was praise for Murderbot.

For reasons due entirely to my apparent failures of reading comprehension, I was expecting a book starring, basically, HK-47 from Knights of the Old Republic. A robot clanking around, calling people meatbags, wanting to be left along, and so on.

The actual books are so much better than that. Instead, it’s a story about your new neurodivergent best friend, trying to figure themselves out and be left alone while they do it. It’s one of the very best uses of robots as a metaphor for something else I’ve ever seen, and probably the first new take on “what do we use robots for besides an Asimov riff” since Blade Runner. It was not what I expected at all, or really in the mood for at the time, and I still immediately bought the next book.

Some other MoonKnights not worth typing the whole titles of

All pumped after the Lumire/Smallwood stuff, I picked up a few other more recent MoonKnights. I just went downstairs and flipped through them again, and I don’t remember a single thing about them. They were fine, I guess?

The Sandman by Neil Gaiman and others

Inspired by the Netflix show (capsule review: great casting, visually as dull as dishwater, got better the more it did it’s own thing and diverged from the books) I went back and read the original comic run for the first time since the turn of the century. When I was in college, there was a cohort of mostly gay, mostly goth kids for whom Sandman was everything. I was neither of those things, but hung out in the subcultures next door, as you will. I liked it fine, and probably liked it more that I would normally have because of how many good friends loved it.

Nearly three decades later, I had a very similar reaction. It always worked best when it moved towards more of an light-horror anthology, where a rotating batch of artists would illustrate stories where deeply weird things happened and then Morpheus would show up at the end and go “wow, that’s messed up.” There’s a couple of things that—woof—haven’t aged super well? Overall, though, still pretty good.

Mostly, though, it made me nostalgic for those people I used to know who loved it so much. I hope they’re all doing well!

Death, the Deluxe Edition

Everything I had to say about Sandman goes double for Death.

Sandman Overture by Neil Gaiman and J.H. Williams III

I never read this when it came out, but I figured as long as I was doing a clean sweep of the Sandman, it was time to finally read it. A lot of fun, but I don’t believe for a hot second this is what Gaiman had in mind when he wrote the opening scene of the first issue back in the late 80s.

The art, though! The art on the original series operated on a spread from “pretty good” to “great for the early 90s”. No insult to the artists, but what the DC production pipeline and tooling could do at the time was never quite up to what Sandman really seemed to call for. And, this is still well before “what if every issue had good art, tho” was the standard for American comics.

The art here is astounding. Page after page of amazing spreads. You can feel Gaiman nodding to himself, thinking “finally! This was how this was always supposed to look.”

Iron Widow by Xiran Jay Zhao

Oh heck yes, this is the stuff. A (very) loose retelling of the story of Wu Zeitan, the first and only female Chinese emperor, in a futuristic setting where animal-themed mechs have Dragonball Z fights. It’s the sort of book where you know exactly how it’s going to end, but the fun is seeing how the main character pulls it off. I read it in one sitting.

Dungeons & Dragons Spelljammer: Adventures in Space

Oh, what a disappointment.

Let’s back up for a sec. Spelljammer was an early-90s 2nd Edition D&D setting, which boiled down to essentially “magical sailing ships in space, using a Ptolemaic-style cosmology. It was a soft replacement for the Manual of the Planes, as a way to link campaign worlds together and provide “otherworldly“ adventures without having to get near the demons and other supernatural elements that had become a problem during the 80s “satanic panic.” (It would ultimately be replaced by Planescape, which brought all that back and then some.)

Tone-wise, Spelljammer was basically “70s van art”. It was never terribly successful, and thirty years on it was mostly a trivia answer, although fondly remembered by a small cadre of aging geeks. As should be entirely predictable, I loved it.

Initially, 5th edition wasn’t interested in past settings others that the deeply boring Forgotten Realms. But as the line continued, and other settings started popping back up, Spelljammer started coming up. What if? And then, there it was.

For the first time in the game’s history, 5th edition found a viable product strategy: 3 roughly 225 to 250-page hardcovers a year, two adventures, one some kind of rules expansion. The adventures occasionally contained a new setting, but the setting was always there to support the story, rather than the other way around.

Spelljammer was going to be different: a deluxe boxed set with a DM screen and three 64-page hardcovers, a setting and rules book, a monster book, and an adventure. (Roughly mirroring the PHB, DMG, MM core books.)

The immediate problem will be obvious to anyone good at mental arithmetic, which is that as a whole the product was 30 to 60 pages shorter than normal, and it felt like it. Worse, the structure of the three hardbacks meant that the monster book and adventure got way more space than they needed, crushing the actual setting material down even further.

As a result, there’s so much that just isn’t there. The setting is boiled down to the barest summary; all the chunky details are gone. As the most egregious example, in the original version The Spelljammer is a legendary ship akin to the flying dutchman, that ship makes up the background of the original logo. The Spelljammer herself isn’t even mentioned in the new version.

Even more frustrating, what is here is pretty good. They made some very savvy changes to better fit with everything else (Spelljammers now travel through the “regular” astral plane instead of “the phogiston” for example). But overall it feels like a sketch for what a 5E spelljammer could look line instead of a finished product.

This is exacerbated by the fact that this release also contains most of a 5E Dark Sun. One of the worst-kept secrets in the industry was that Hasbro had a 5E Dark Sun book under development that was scrapped before release. The races and creatures from that effort ended up here. Dark Sun also gets an amazing cameo: the adventure includes a stop in “Doomspace”, a solar system where the star has become a black hole, and the inhabited planet is just on the cusp of being sucked in. While the names are all slightly changed, this is blatantly supposed to be the final days of Athas. While I would have been first in line to pick up a 5E Dark Sun, having the setting finally collapse in on itself in another product entirely is a perfect end to the setting. I kind of loved it.

Finally, Spelljammer had some extremely racist garbage in it. To the extent that it’s hard to believe that these book had any editorial oversight at all. For a product that had the physical trappings (and price) of a premium product, the whole package came across as extremely half-assed. Nowhere more so that in the fact that they let some white supremacist shit sail through unnoticed.

Spelljammer, even more so than the OGL shitshow, caused me fundamentally reassess my relationship with the company that owns D&D. I still love the game, but I’m going to need to prove it to me before I buy anything else from them. Our support should be going elsewhere.

Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands by Kate Beaton

Back during the mid-00s webcomics boom, there were a lot of webcomics that were good for webcomics, but a much smaller set that were good for comics, full stop. Kate Beaton’s Hark a Vagrant! stood head and shoulders above that second group.

Most of the people who made webcomics back then have moved on, using their webcomic to open doors to other—presumably better paying—work. Most of them have moved on from the styles from their web work. To use one obvious and slightly cheap example, Ryan North’s Squirrel Girl has different panels on each page, you know?

One of the many, many remarkable things about Ducks is that is’s recognizably the same style as Hark a Vagrant!, just deployed for different purpose. All her skills as a storyteller and and cartoonist are on display here, her ability to capture expressions with only a few lines, the sharp wit, the impeccable timing, but this book is not even remotely funny.

It chronicles the years she spent working on the Oil Sands in Alberta. A strange, remote place, full of people, mostly men, trying to make enough money to leave.

Other than a brief introduction, the book has no intrusions from the future, there’s no narration contextualizing the events. Instead, it plays out as a series of vignettes of her life there, and she trusts that the reader is smart enough to understand why she’s telling these stories in this order.

It’s not a spoiler, or much of one anyway, to say that a story about a young woman in a remote nearly all-male environment goes the way you hope it doesn’t. There’s an incredible tension to the first half of the book where you know something terrible is going to happen, it’s a horrible relief when it finally does.

As someone closer in age to her parents than her when this all happened, I found myself in a terrible rage at them as I read it—how could you let her do this? How could you let this happen? But they didn’t know. And there was nothing they could do.

It was, by far, the best book I read last year. It haunts my memory.

Jenny Sparks: The Secret History of the Authority by a bunch of hacks

I loved the original run on The Authority 20 years ago, and Jenny Sparks is one of my all-time favorite comic book characters, but I had never read Millar’s prequel miniseries about her. I picked up a copy in a used bookstore. I wish I hadn’t. It was awful.

She-Hulk omnibus 1 by Dan Slot et al

Inspired by the Disney+ show (which I loved) I picked up the first collection of the early-00s reboot of She-Hulk. I had never read these, but I remember what a great reception they got at the time. But… this wasn’t very good? It was far too precious, the 4th wall breaking way too self-conscious. A super-hero law firm with a basement full of every marvel comic as a caselaw library is a great one-off joke, but a terrible ongoing premise. The art was pretty good, though.

She-Hulk Epic Collection: Breaking the Fourth Wall by John Byrne, Steve Gerber, and Others

On the other hand, this is the stuff. Byrne makes the 4th wall breaks look easy, and there’s at joy and flow to the series that the later reboots lack. She-Hulk tearing out of the page and screaming in rage at the author is an absolutes delight. And then, when Byrne leaves, he’s replaced by Steve “Howard the Duck” Gerber, and it got even better,

Valuable Humans in Transit and other stories by qntm

This short story collection inclues the most upsetting horror story I’ve ever read, Lena, and the sequel, which manages to be even worse. Great writing, strongly recommended.

Good Adaptations and the Lord of the Rings at 20 (and 68)

What makes a good book-to-movie adaptation?

Or to look at it the other way, what makes a bad one?

Books and movies are very different mediums and therefore—obviously—are good at very different things. Maybe the most obvious difference is that books are significantly more information-dense than movies are, so any adaptation has to pick and choose what material to keep.

The best adaptations, though, are the ones that keep the the themes and characters—what the book is about— and move around, eliminate, or combine the incidents of the plot to support them. The most successful, like Jaws or Jurassic Park for example, are arguably better than their source material, jettisoning extraneous sideplots to focus on the main concepts.

Conversely, the worst adaptations are the ones that drop the themes and change the point of the story. Stephen King somewhat famously hates the movie version of The Shining because he wrote a very personal book about his struggle with alcoholism disguised as a haunted hotel story, and Kubrick kept the ghosts but not the rest. The movie version of The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy was made by people who thought the details of the plot were more important than the jokes, rather than the other way around, and didn’t understand why the Nutrimat was bad.

And really, it’s the themes, the concepts, the characters, that make stories appeal to us. It’s not the incidents of the plot we connect to, it’s what the story is about. That’s what we make the emotional connection with.

And this is part of what makes a bad adaptation so frustrating.

While the existence of a movie doesn’t erase the book it was based on, it’s a fact that movies have higher profiles, reach bigger audiences. So it’s terribly disheartening to have someone tell you they watched a movie based on that book you like that they didn’t read, when you know all the things that mattered to you didn’t make it into the movie.

And so we come to The Lord of the Rings! The third movie, Return of the King turned 20 this week, and those movies are unique in that you’ll think they’re either a fantastic or a terrible adaptation based on which character was your favorite.

Broadly speaking, Lord of the Rings tells two stories in parallel. The first, is a big epic fantasy, with Dark Lords, and Rings of Power, and Wizards, and Kings in Exile. Strider is the main character of this story, with a supporting cast of Elves, Dwarves, and Horse Vikings. The second is a story about some regular guys who are drawn into a terrifying and overwhelming adventure, and return home, changed by the experience. Sam is the main character of the second story, supported by the other Hobbits.

(Frodo is an interestingly transgressive character, because he floats between the two stories, never committing to either. But that’s a whole different topic.)

And so the book switches modes based on which characters are around. The biggest difference between the modes is the treatment of the Ring. When Strider or Gandalf or any other character from the first story are around, the Ring is the most evil thing in existence—it has to be. So Gandalf refuses to take it, Galadriel recoils, it’s a source of unstoppable corruption.

But when it’s just the Hobbits, things are different. That second story is both smaller and larger at the the same time—constantly cutting the threat of the Ring off at the knees by showing that there are larger and older things than the Ring, and pointing out thats it’s the small things really matter. So Tom Bombadil is unaffected, Faramir gives it back without temptation, Sam sees the stars through the clouds in Mordor. There are greater beauties and greater powers than some artifact could ever be.

This is, to be clear, not a unique structure. To pull an obvious example, Star Wars does the same thing, paralleling Luke’s kid from the sticks leaving home and growing into his own person with the epic struggle for the future of the entire galaxy between the Evil Galactic Empire and the Rebel Alliance. In keeping with that movie’s clockwork structure, Lucas manages to have the climax of both stories be literally the exact same moment—Luke firing the torpedoes into the exhaust port.

Tolkien is up to something different however, and climaxes his two stories fifty pages apart. The Big Fantasy Epic winds down, and then the cast reduces to the Hobbits again and they go home, where they have to use everything they’ve learned to solve their own problems instead of helping solve somebody else’s.

In my experience, everyone connects more strongly with one of the two stories. The tends to boil down to who your favorite character is—Strider or Sam. Just about everyone picks one of those two as their favorite. It’s like Elvis vs. The Beatles; most people like both, but everyone has a preference.

(And yeah, there’s always some wag that says Boromir/The Who.)

Just to put all my cards on the table, my favorite character is Sam. (And I prefer The Beatles.)

Based on how the beginning and end of the books work, it seems clear that Tolkien thought of that story—the regular guys being changed by the wide world story—as the “main one”, and the Big Epic was there to provide a backdrop.

There’s an entire cottage industry of people explaining what “Tolkien really meant” in the books, and so there’s not a lot of new ground to cover there, so I’ll just mention that the “regular dudes” story is clearly the one influenced—not “based on”, but influenced—by his own WWI experiences and move on.

Which brings us back to the movies.

Even with three very long movies, there’s a lot more material in the books than could possibly fit. And, there’s an awful lot of things that are basically internal or delivered through narration that need dramatizing in a physical way to work as a film.

So the filmmakers made the decision to adapt only that first story, and jettison basically everything from the second.

This is somewhat understandable? That first story has all the battles and orcs and wargs and wizards and things. That second story, if you’re coming at it from the perspective of trying to make an action movie, is mostly Sam missing his garden? From a commercial point of view, it’s hard to fault the approach. And the box office clearly agreed.

And this perfectly explains all the otherwise bizarre changes. First, anything that undercuts the Ring has to go. So, we cut Bombadil and everything around him for time, yes, but also we can’t have a happy guy with a funny hat shake off the Ring in the first hour before Elrond has even had a chance to say any of the spooky lines from the trailer. Faramir has to be a completely different character with a different role. Sam and Frodo’s journey across the plains of Mordor has to play different, becase the whole movie has to align on how terrible the Ring is, and no stars can peek through the clouds to give hope, no pots can clatter into a crevasse to remind Sam of home. Most maddeningly, Frodo has to turn on Sam, because the Ring is all-powerful, and we can’t have an undercurrent showing that there are some things even the Ring can’t touch.

In the book, Sam is the “hero’s journey” characer. But, since that whole story is gone, he gets demoted to comedy sidekick, and Aragorn is reimagined into that role, and as such needs all the trappings of the Hero with a Thousand Faces retrofitted on to him. Far from the confident, legendary superhero of the books, he’s now full of doubt, and has to Refuse the Call, have a mentor, cross A Guarded Threshold, suffer ordeals, because he’s now got to shoulder a big chunk of the emotional storytelling, instead of being an inspirational icon for the real main characters.

While efficient, this all has the effect of pulling out the center of the story—what it’s about.

It’s also mostly crap, because the grafted-on hero’s journey stuff doesn’t fit well. Meanwhile, one of the definitive Campbell-style narratives is lying on the cutting room floor.

One of the things that makes Sam such a great character is his stealth. He’s there from the very beginning, present at every major moment, an absolutely key element in every success, but the book keeps him just out of focus—not “off stage”, but mostly out of the spotlight.

It’s not until the last scene—the literal last line—of the book that you realize that he was actually the main character the whole time, you just didn’t notice.

The hero wasn’t the guy who became King, it was the guy who became mayor.

He’s why my laptop bag always has a coil of rope in the side pocket—because you’ll want if if you don’t have it.

(I also keep a towel in it, because it’s a rough universe.)

And all this is what makes those movies so terribly frustrating—because they are an absolutely incredible adaptation of the Epic Fantasy parts. Everything looks great! The design is unbelievable! The acting, the costumes, the camera work. The battles are amazing. Helm’s Deep is one of those truly great cinematic achievements. My favorite shot in all three movies—and this is not a joke—is the shot of the orc with the torch running towards the piled up explsoves to breach the Deeping Wall like he’s about to light the olympic torch. And, in the department of good changes, the cut down speech Theoden gives in the movie as they ride out to meet the invaders—“Ride for ruin, Ride for Rohan!”—is an absolutely incredible piece of filmmaking. The Balrog! And, credit where credit is due, everything with Boromir is arguably better than in the book, mostly because Sean Bean makes the character into an actual character instead of a walking skepticism machine.

So if those parts were your jam, great! Best fantasy movies of all time! However, if the other half was your jam, all the parts that you connected to just weren’t there.

I’m softer on the “breakdancing wizards” fight from the first movie than a lot of fellow book purists, but my goodness do I prefer Gandalf’s understated “I liked white better,” over Magneto yelling about trading reason for madness. I understand wanting to goose the emotion, but I think McKellen could have made that one sing.

There’s a common complaint about the movie that it “has too many endings.” And yeah, the end of the movie version of Return of the King is very strange, playing out a whole series of what amount to head-fake endings and then continuing to play for another half an hour.

And the reason is obvious—the movie leaves the actual ending out! The actual ending is the Hobbits returning home and using everything they’ve learned to save the Shire; the movie cuts all that, and tries to cobble a resolution of out the intentionally anti-climactic falling action that’s supposed to lead into that.

Lord of the Rings: the Movie, is a story about a D&D party who go on an exciting grueling journey to destroy an evil ring, and then one of them becomes the King. Lord of the Rings: the Book, is a story about four regular people who learn a bunch of skills they don’t want to learn while doing things they don’t want to do, and then come home and use those skills to save their family and friends.

I know which one I prefer.

What makes a good adaptation? Or a bad one?

Does it matter if the filmmaker’s are on the same page as the author?

What happens when they’re only on the same page with half of the audience?

The movies are phenomenally well made, incredibly successful films that took one of the great heros of fiction and sandblasted him down to the point where there’s a whole set of kids under thirty who think his signature moment was yelling “po-TAY-toes” at some computer animation.

For the record: yes, I am gonna die mad about it.

Layoff Season(s)

Well, it’s layoff season again, which pretty much never stopped this year? I was going to bury a link or two to an article in that last sentence, but you know what? There’s too many. Especially in tech, or tech-adjacent fields, it’s been an absolute bloodbath this year.

So, why? What gives?

I’ve got a little personal experience here: I’ve been through three layoffs now, lost my job once, shoulder-rolled out of the way for the other two. I’ve also spent the last couple decades in and around “the tech industry”, which here we use as shorthand for companies that are either actually a Silicon Valley software company, or a company run by folks that used to/want to be from one, with a strong software development wing and at least one venture capital–type on the board.

In my experience, Tech companies are really bad at people. I mean this holistically: they’re bad at finding people, bad at hiring, and then when they do finally hire someone, they’re bad at supporting those people—training, “career development”, mentoring, making sure they’re in the right spot, making sure they’re successful. They’re also bad any kind of actual feedback cycle, either to reward the excellent or terminate underperformers. As such, they’re also bad at keeping people. This results in the vicious cycle that puts the average time in a tech job at about 18 months—why train them if they’re gonna leave? Why stay if they won’t support me?

There are pockets where this isn’t true, of course; individual managers, or departments, or groups, or even glue-type individuals holding the scene together that handle this well. I think this is all a classic “don’t attribute to malice what you can attribute to incompetence” situtation. I say this with all the love in the world, but people who are good at tech-type jobs tend to be low-empathy lone wolf types? And then you spend a couple decades promoting the people from that pool, and “ask your employees what they need” stops being common sense and is suddenly some deep management koan.

The upshot of all this is that most companies with more than a dozen or two employees have somewhere between 10–20% of the workforce that isn’t really helping out. Again—this isn’t their fault! The vast majority of those people would be great employees in a situation that’s probably only a tiny bit different than the one you’re in. But instead you have the one developer who never seems to get anything done, the other developer who’s work always fails QA and needs a huge amount of rework, the person who only seems to check hockey scores, the person whos always in meetings, the other person whose always in “meetings.” That one guy who always works on projects that never seem to ship.1 The extra managers that don’t seem to manage anyone. And, to be clear, I’m talking about full-time salaried people. People with a 401(k) match. People with a vesting schedule.

No one doing badly enough to get fired, but not actually helping row the boat.

As such, at basically any point any large company—and by large I mean over about 50—can probably do a 10% layoff and actually move faster afterwards, and do a 20% layoff without any significant damage to the annual goals—as long as you don’t have any goals about employee morale or well-being. Or want to retain the people left.

The interesting part—and this is the bad interesting, to be clear—is if you can fire 20% of your employees at any time, when do you do that?

In my experience, there’s two reasons.

First, you drop them like a submarine blowing the ballast tanks. Salaries are the biggest expense center, and in a situation where the line isn’t going up right, dropping 20% of the cost is the financial equivalent of the USS Dallas doing an emergency surface.

Second, you do it to discipline labor. Is the workforce getting a little restless? Unhappy about the stagnat raises? Grumpy about benefits costing more? Is someone waving around a copy of Peopleware?2 Did the word “union” float across the courtyard? That all shuts down real fast if all those people are suddenly sitting between two empty cubicles. “Let’s see how bad they score the engagement survey if the unemployment rate goes up a little!” Etc.

Again—this is all bad! This is very bad! Why do any this?

The current wave feels like a combo plate of both reasons. On the one hand, we have a whole generation of executive leaders that have never seen interest rates go up, so they’re hitting the one easy panic button they have. But mostly this feels like a tantrum by the c-suite class reacting to “hot labor summer” becoming “eternal labor september.”

Of course, this is where I throw up my hands and have nothing to offer except sympathy. This all feels so deeply baked in to the world we live in that it seems unsolvable short of a solution that ends with us all wearing leather jackets with only one sleve.

So, all my thoughts with everyone unexpectedly jobless as the weather gets cold. Hang on to each other, we’ll all get through this.

-

At one point in my “career”, the wags in the cubes next to mine made me a new nameplate that listed my job as “senior shelf-ware engineer.” I left it up for months, because it was only a little bit funny, but it was a whole lot true.

-

That one was probably me, sorrryyyyyy (not sorry)

Re-Capturing the Commons

The year’s winding down, which means it’s time to clear out the drafts folder. Let me tell you about a trend I was watching this year.

Over the last couple of decades, a business model has emerged that looks something like this:

- A company creates a product with a clear sales model, but doesn’t have value without a strong community

- The company then fosters such a community, which then steps in and shoulders a fair amount of the work of running said community

- The community starts creating new things on top of what that original work of the parent company—and this is important—belong to those community members, not the company

- This works well enough that the community starts selling additional things to each other—critically, these aren’t competing with that parent company, instead we have a whole “third party ecosystem”.

(Hang on, I’ll list some examples in a second.)

These aren’t necessarily “open source” from a formal OSI “Free & Open Source Software” perspective, but they’re certainly open source–adjacent, if you will. Following the sprit, if not the strict legal definition.

Then, this year especially, a whole bunch of those types of companies decided that they wouldn’t suffer anyone else makining things they don’t own in their own backyard, and tried to reassert control over the broader community efforts.

Some specific examples of what I mean:

- The website formerly known as Twitter eliminating 3rd party apps, restricting the API to nothing, and blocking most open web access.

- Reddit does something similar, effectively eliminates 3rd party clients and gets into an extended conflict with the volunteer community moderators.

- StackOverflow and the rest of the StackExchange network also gets into an extended set of conflicts with its community moderators, tries to stop releasing the community-generated data for public use, revises license terms, and descends into—if you’ll forgive the technical term—a shitshow.

- Hasbro tries to not only massively restrict the open license for future versions of Dungeons and Dragons, but also makes a move to retroactively invalidate the Open Game License that covered material created for the 3rd and 5th editions of the game over the last 20 years.

And broadly, this is all part of the Enshittification Curve story. And each of these examples have a whole set of unique details. Tens, if not hundreds of thousands of words have been written on each of these, and we don’t need to re-litigate those here.

But there’s a specific sub-trend here that I think is worth highlighting. Let’s look at what those four have in common:

- Each had, by all accounts, a successful business model. After-the-fact grandstanding non-withstanding, none of those four companies was in financial trouble, and had a clear story about how they got paid. (Book sales, ads, etc.)

- They all had a product that was absolutely worthless without an active community. (The D&D player’s handbook is a pretty poor read if you don’t have people to play with, reddit with no comments is just an ugly website, and so on)

- Community members were doing significant heavy lifting that the parent company was literally unable to do. (Dungeon Mastering, community moderating. Twitter seems like the outlier here at first glance, but recall that hashtags, threads, the word “tweet” and literally using a bird as a logo all came from people not on twitter’s payroll.)

- There were community members that made a living from their work in and around the community, either directly or indirectly. (3rd party clients, actual play streams, turning a twitter account about things your dad says into a network sitcom. StackOverflow seems like the outlier on this one, until you remember that many, many people use their profiles there as a kind of auxiliary outboard resume.)

- They’ve all had recent management changes; more to the point, the people who designed the open source–adjacent business model are no longer there.

- These all resulted in huge community pushback

So we end up in a place where a set of companies that no one but them can make money in their domains, and set their communities on fire. There was a lot of handwaving about AI as an excuse, but mostly that’s just “we don’t want other people to make money” with extra steps.

To me, the most enlightening one here is Hasbro, because it’s not a tech company and D&D is not a tech product, so the usual tech excuses for this kind of behavior don’t fly. So let’s poke at that one for an extra paragraph or two:

When the whole OGL controversy blew up back at the start of the year, certain quarters made a fair amount of noise about how this was a good thing, because actually, most of what mattered about D&D wasn’t restrict-able, or was in the public domain, and good old fair use was a better deal than the overly-restrictive OGL, and that the community should never have taken the deal in the first place. And this is technically true, but only in the ways that don’t matter.

Because, yes. The OGL, as written, is more restrictive that fair use, and strict adherence to the OGL prevents someone from doing things that should otherwise be legal. But that misses the point.

Because what we’re actually talking about is an industry with one multi-billion dollar company—the only company on earth that has literal Monopoly money to spend—and a whole bunch of little tiny companies with less than a dozen people. So the OGL wasn’t a crummy deal offered between equals, it was the entity with all the power in the room declaring a safe harbor.

Could your two-person outfit selling PDFs online use stuff from Hasbro’s book without permission legally? Sure. Could you win the court case when they sue you before you lose your house? I mean, maybe? But not probably.

And that’s what was great about it. For two decades, it was the deal, accept these slightly more restrictive terms, and you can operate with the confidence that your business, and your house, is safe. And an entire industry formed inside that safe harbor.

Then some mid-level suit at Hasbro decided they wanted a cut?

And I’m using this as the example partly because it’s the most egregious. But 3rd party clients for twitter and reddit were a good business to be in, until they suddenly were not.

And I also like using Hasbro’s Bogus Journey with D&D as the example because that’s the only one where the community won. With the other three here, the various owners basically leaned back in their chairs and said “yeah, okay, where ya gonna go?” and after much rending of cloth, the respective communities of twitter, and reddit, and StackOverflow basically had to admit there wasn’t an alternative., they were stuck on that website.

Meanwhile, Hasbro asked the same question, and the D&D community responded with, basically, “well, that’s a really long list, how do you want that organized?”

So Hasbro surrendered utterly, to the extent that more of D&D is now under a more irrevocable and open license that it was before. It feels like there’s a lesson in competition being healthy here? But that would be crass to say.

Honestly, I’m not sure what all this means; I don’t have a strong conclusion here. Part of why this has been stuck in my drafts folder since June is that I was hoping one of these would pop in a way that would illuminate the situation.

And maybe this isn’t anything more than just what corporate support for open source looks like when interest rates start going up.

But this feels like a thing. This feels like it comes from the same place as movie studios making record profits while saying their negotiation strategy is to wait for underpaid writers to lose their houses?

Something is released into the commons, a community forms, and then someone decides they need to re-capture the commons because if they aren’t making the money, no one can. And I think that’s what stuck with me. The pettiness.

You have a company that’s making enough money, bills are paid, profits are landing, employees are taken care of. But other people are also making money. And the parent company stops being a steward and burns the world down rather than suffer someone else make a dollar they were never going to see. Because there’s no universe where a dollar spent on Tweetbot was going to go to twitter, or one spent on Apollo was going to go to reddit, or one spent on any “3rd party” adventure was going to go to Hasbro.

What can we learn from all this? Probably not a lot we didn’t already know, but: solidarity works, community matters, and we might not have anywhere else to go, but at the same time, they don’t have any other users. There’s no version where they win without us.

2023’s strange box office

Weird year for the box office, huh? Back in July, we had that whole rash of articles about the “age of the flopbuster” as movie after movie face-planted. Maybe things hadn’t recovered from the pandemic like people hoped?

And then, you know, Barbenheimer made a bazillion dollars.

And really, nothing hit like it was supposed to all year. People kept throwing out theories. Elemental did badly, and it was “maybe kids are done with animation!” Ant-Man did badly, and it was “Super-Hero fatigue!” Then Spider-Verse made a ton of money disproving both. And Super Mario made a billion dollars. And then Elemental recovered on the long tail and ended up making half a billion? And Guardians 3 did just fine. But Captain Marvel flopped. Harrison Ford came back for one more Indiana Jones and no one cared.

Somewhere around the second weekend of Barbenheimer everyone seemed to throw up their hands as if to say “we don’t even know what’ll make money any more”.

Where does all that leave us? Well, we clearly have a post-pandemic audience that’s willing to show up and watch movies, but sure seems more choosy than they used to be. (Or choosy about different things?)

Here’s my take on some reasons why:

The Pandemic. I know we as a society have decided to act like COVID never happened, but it’s still out there. Folks may not admit it, but it’s still influencing decisions. Sure, it probably wont land you in the hospital, but do you really want to risk your kid missing two weeks of school just so you can see the tenth Fast and the Furious in the theatre? It may not be the key decision input anymore, but that’s enough potential friction to give you pause.